- Volvo

- Ronin

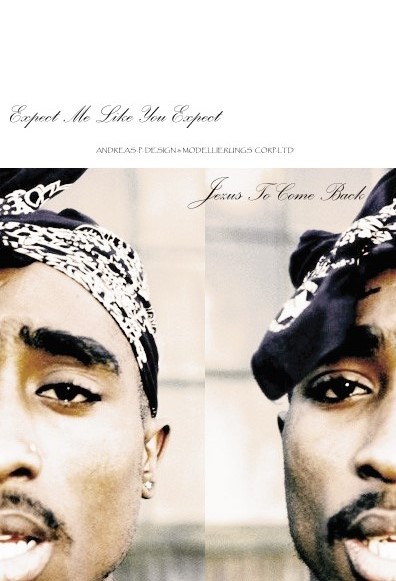

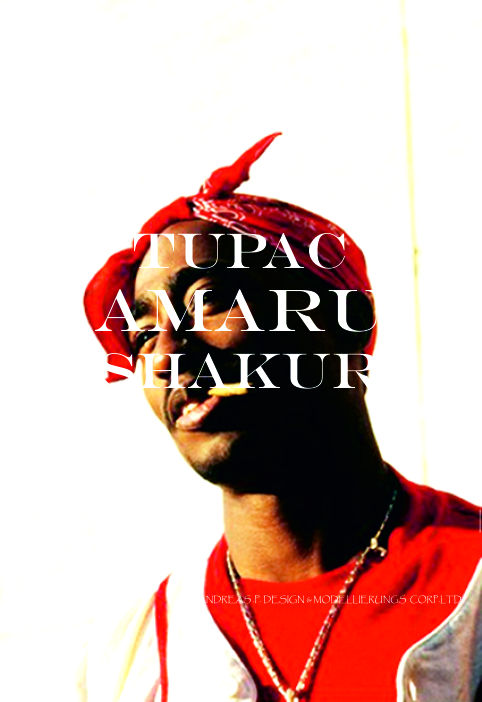

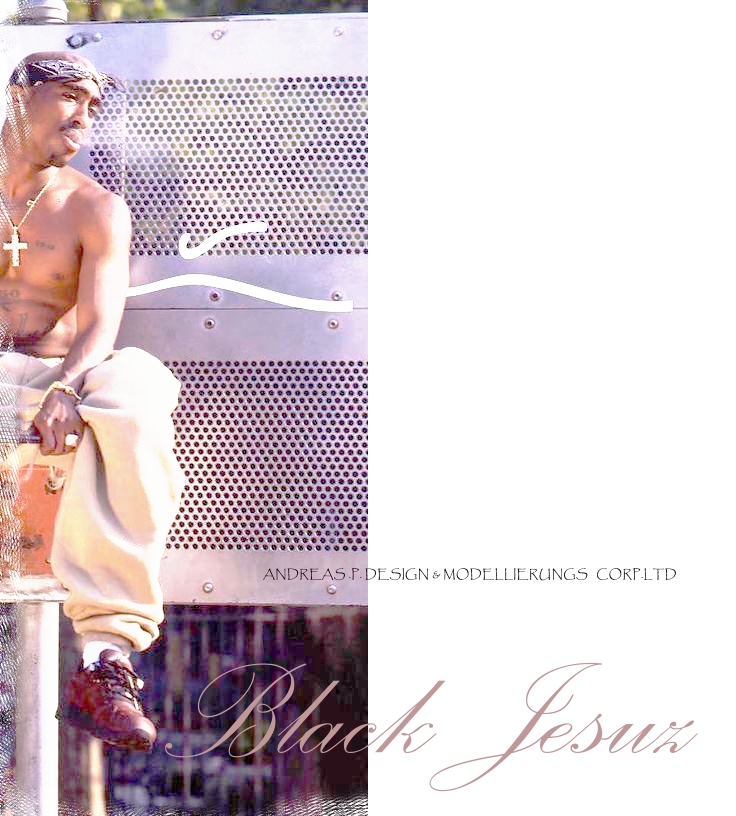

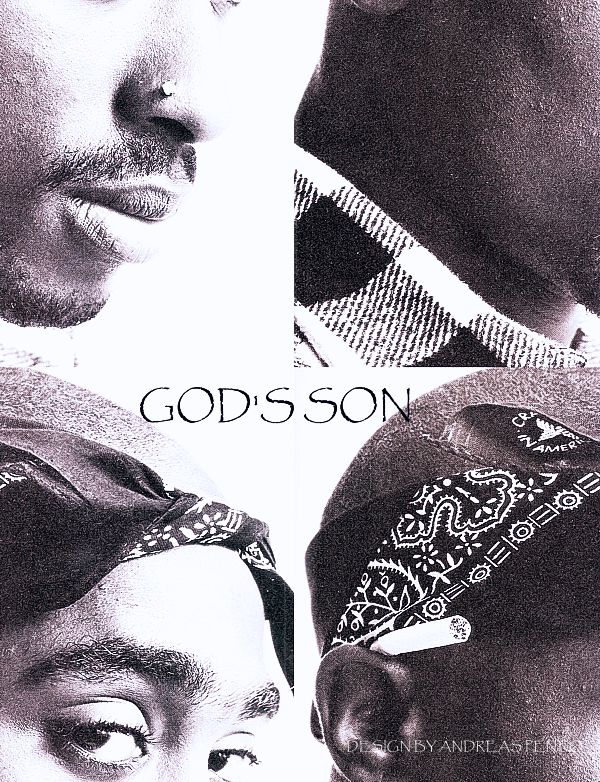

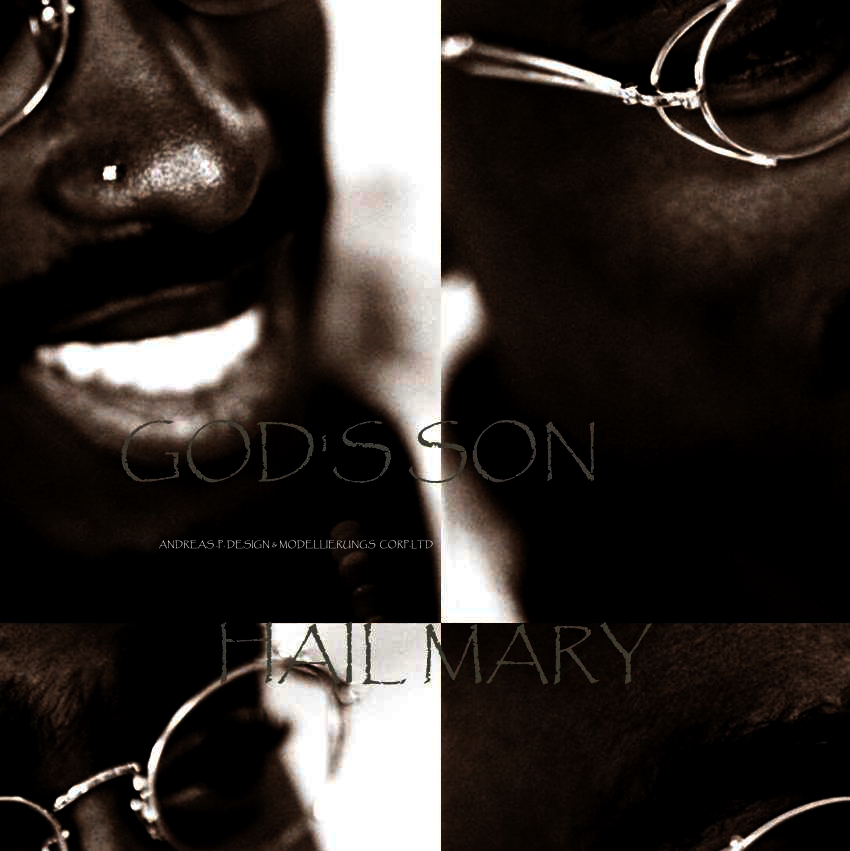

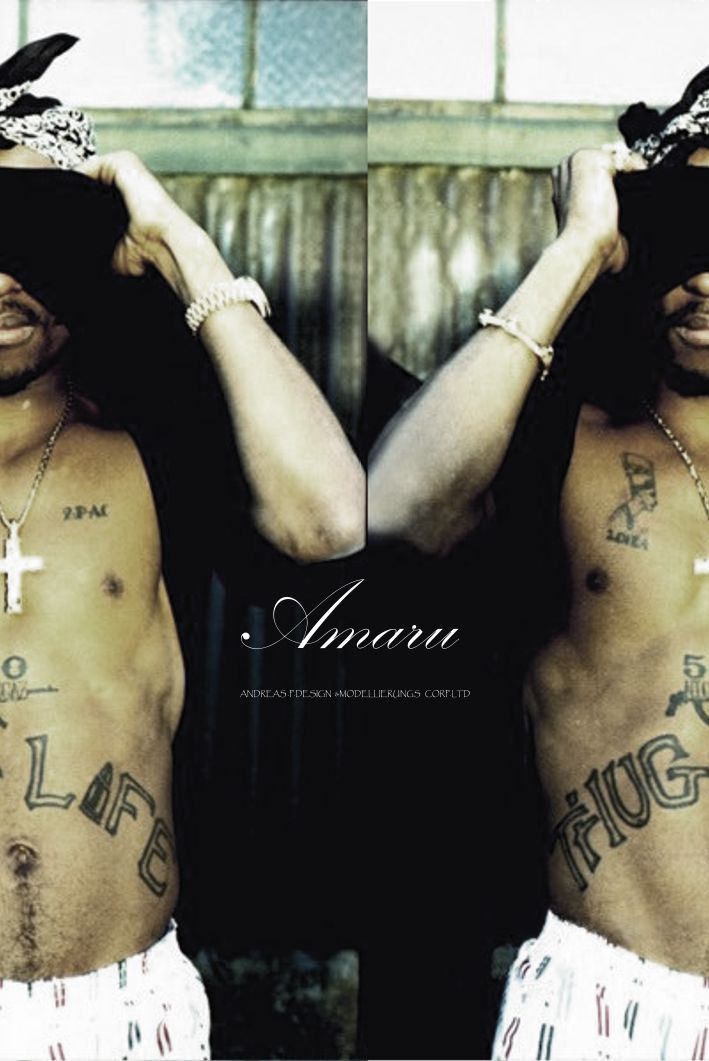

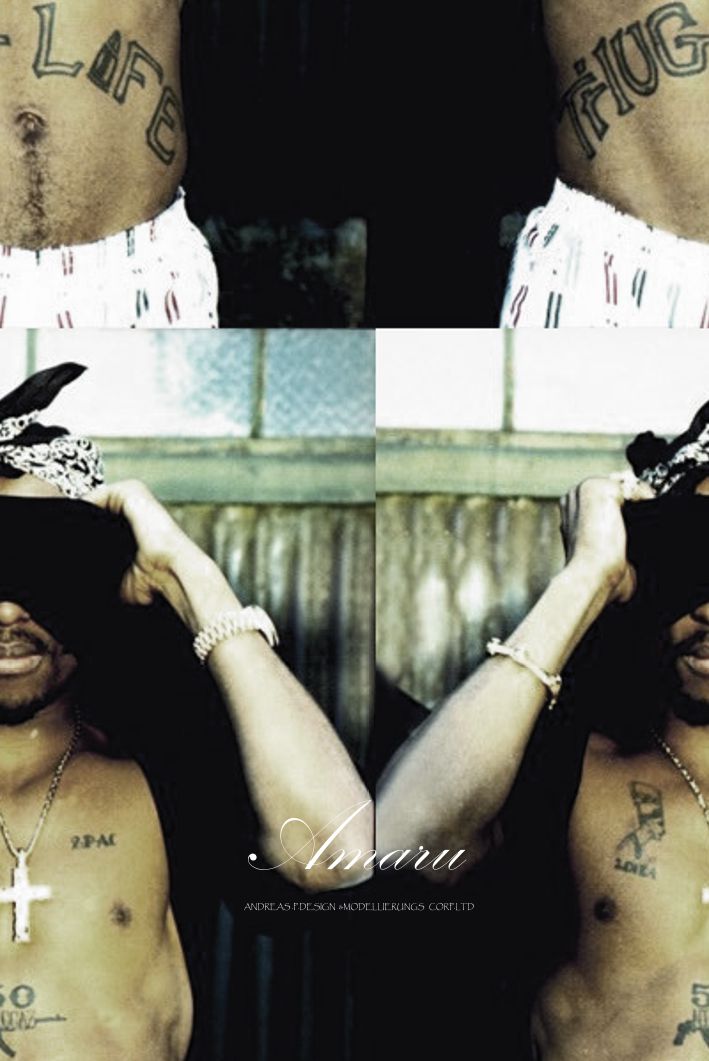

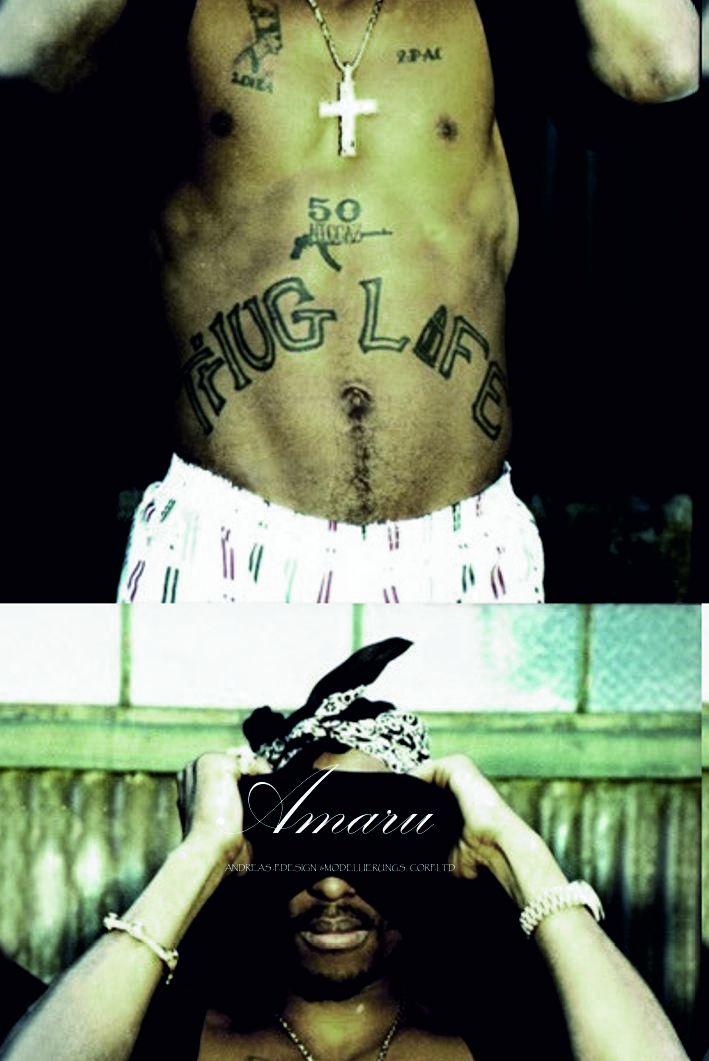

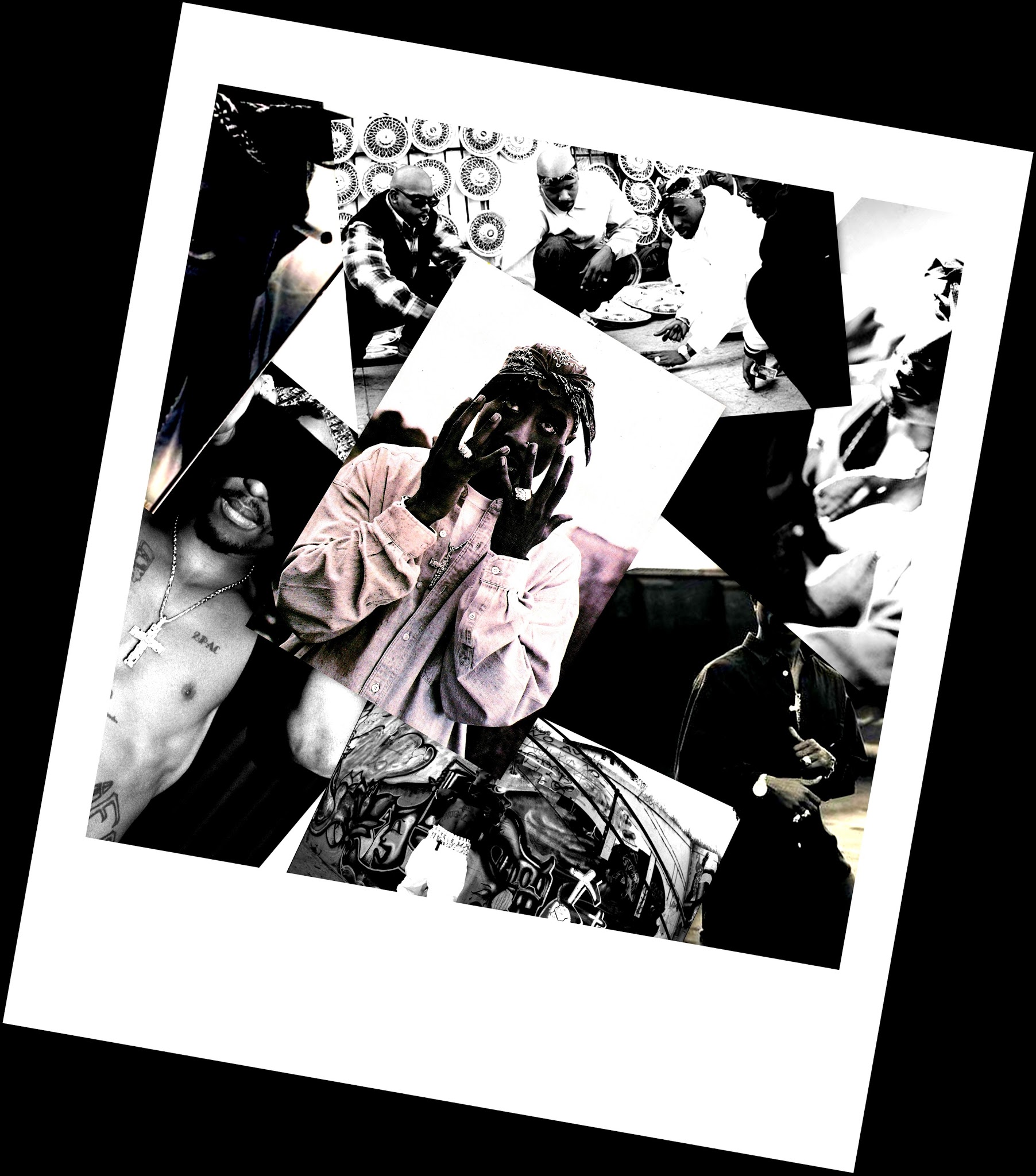

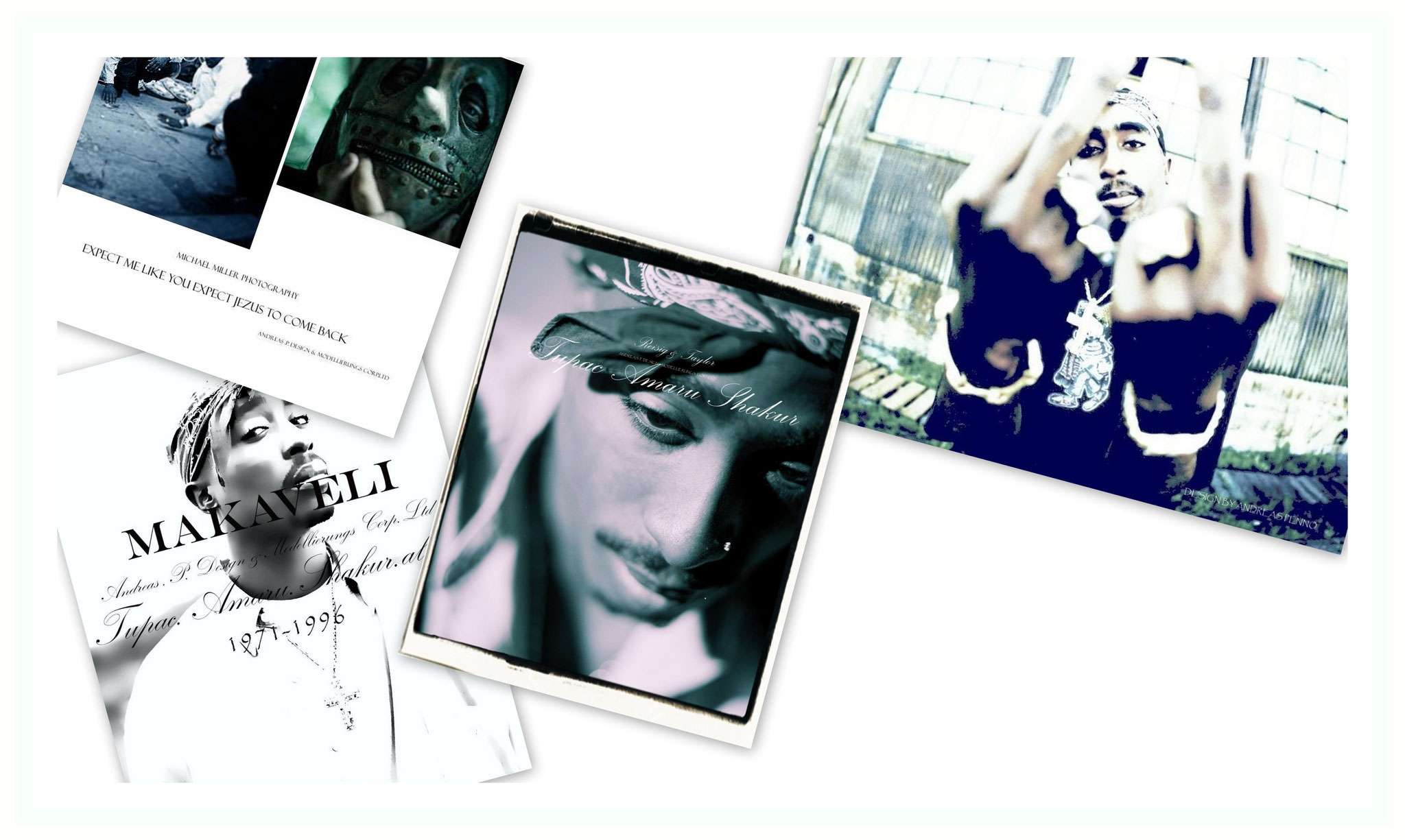

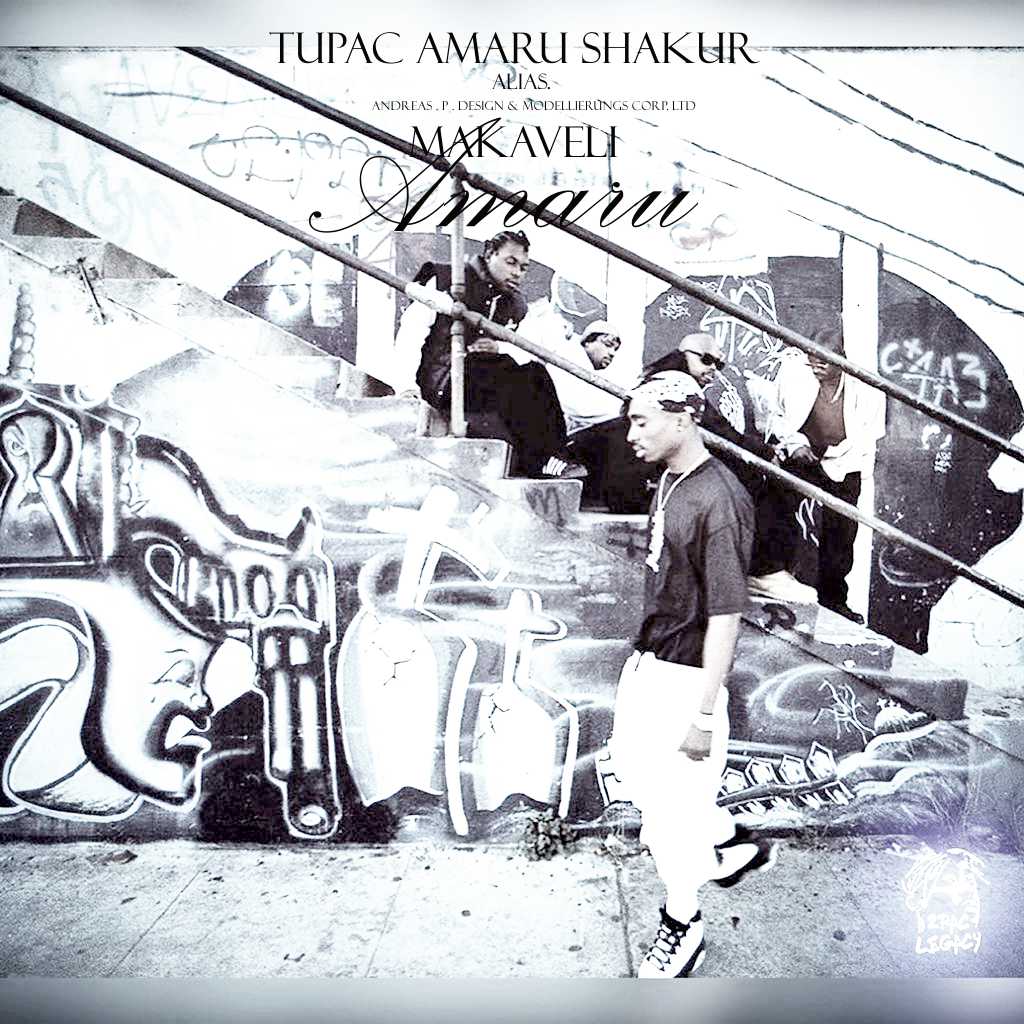

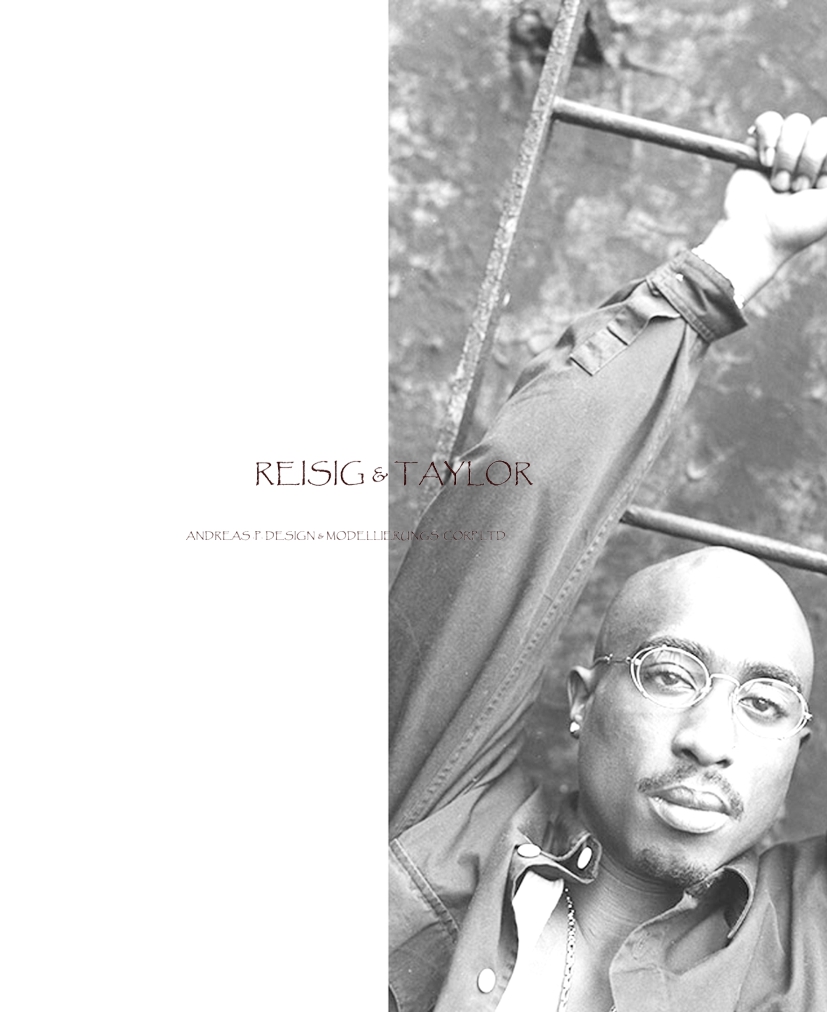

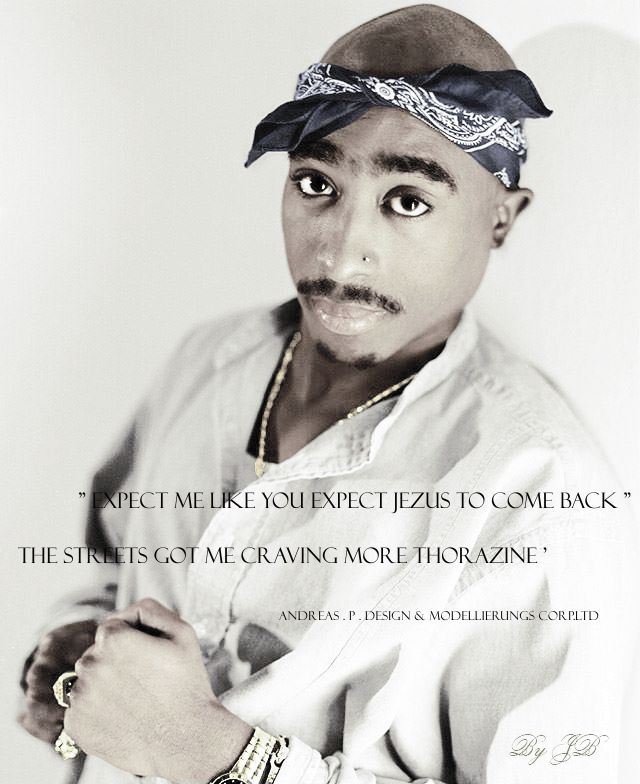

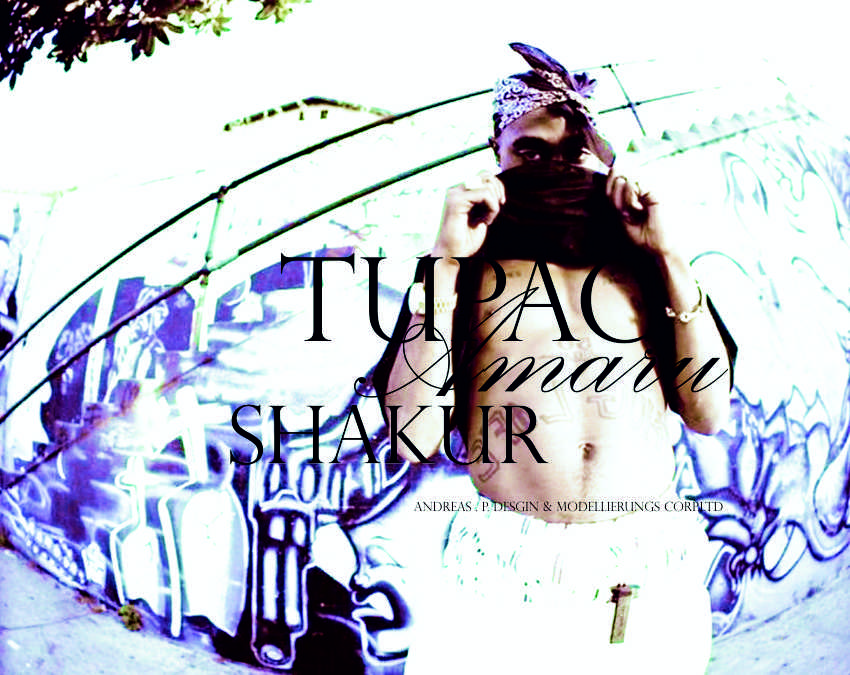

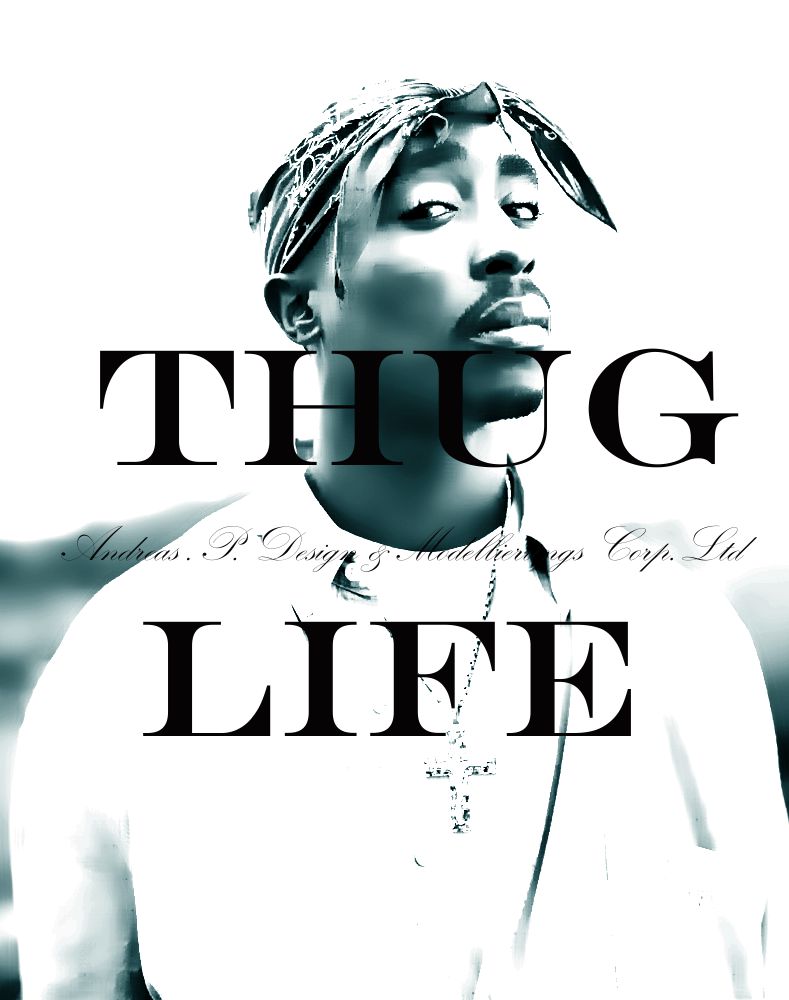

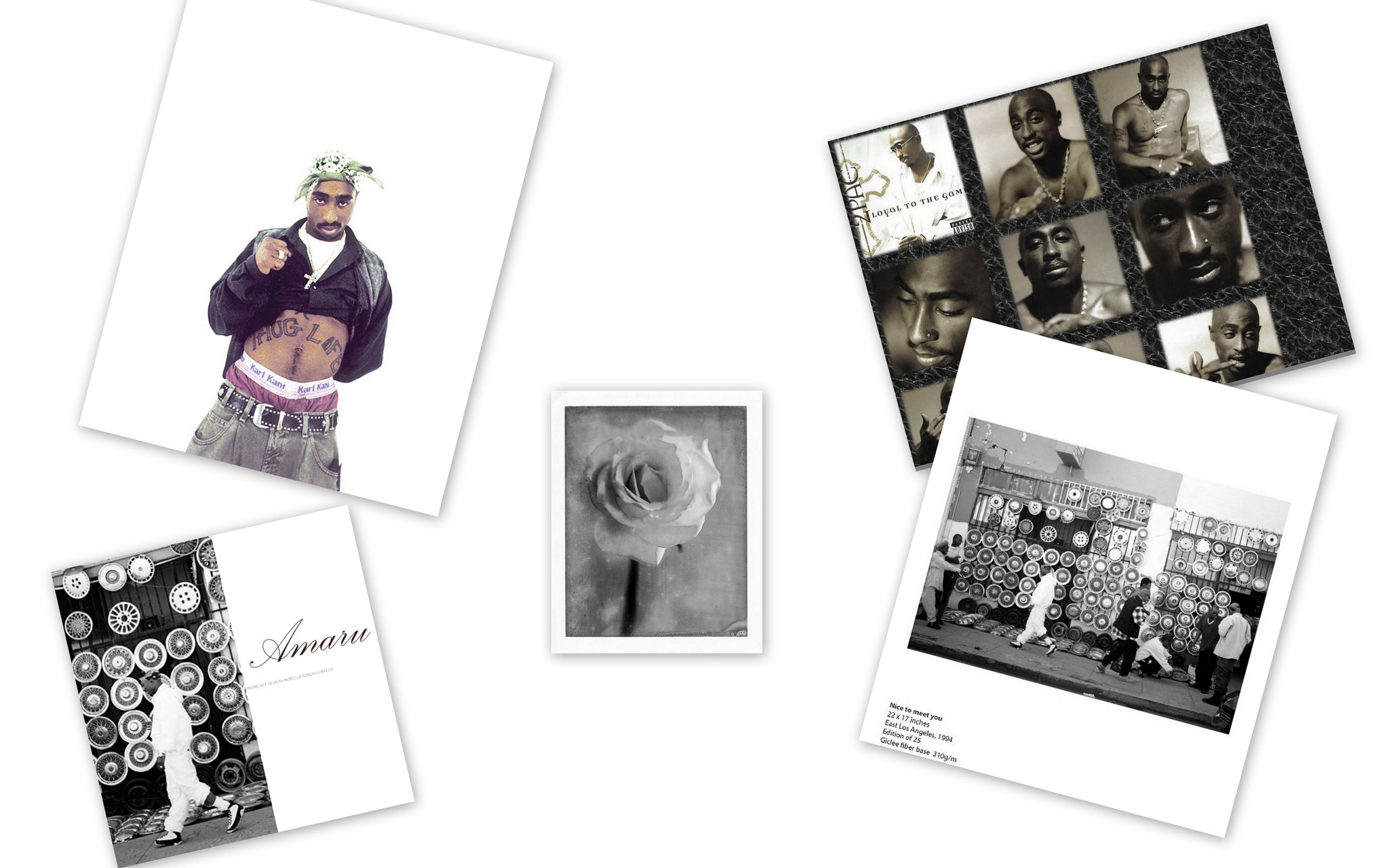

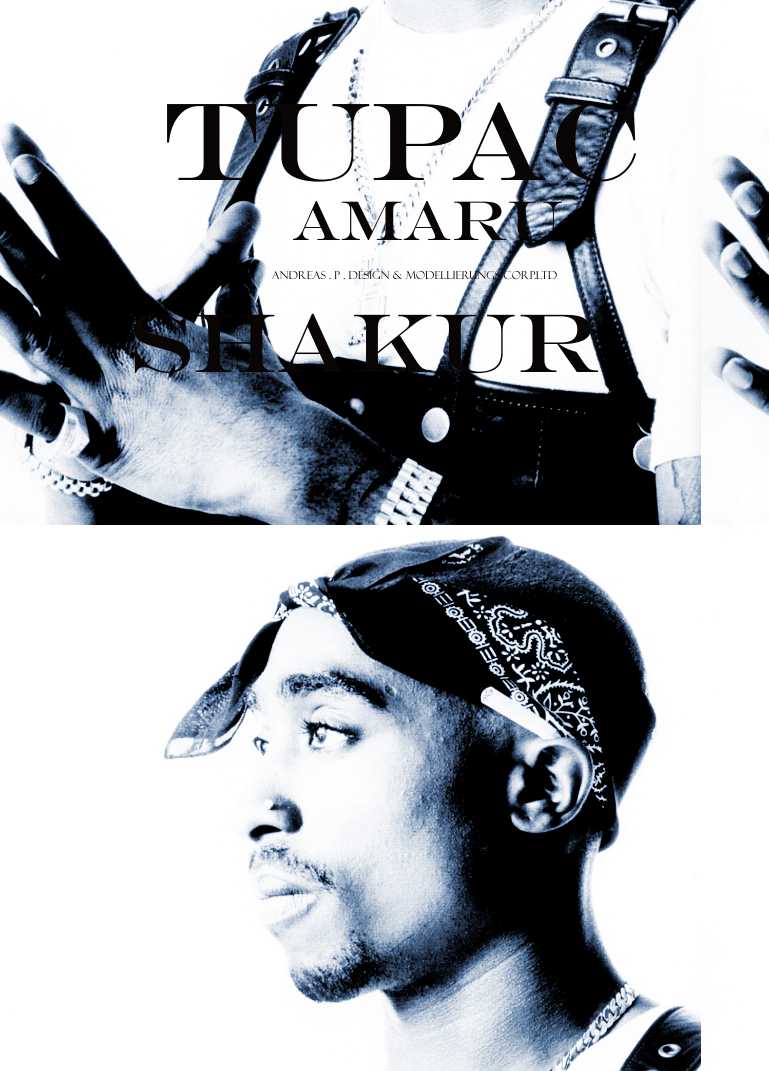

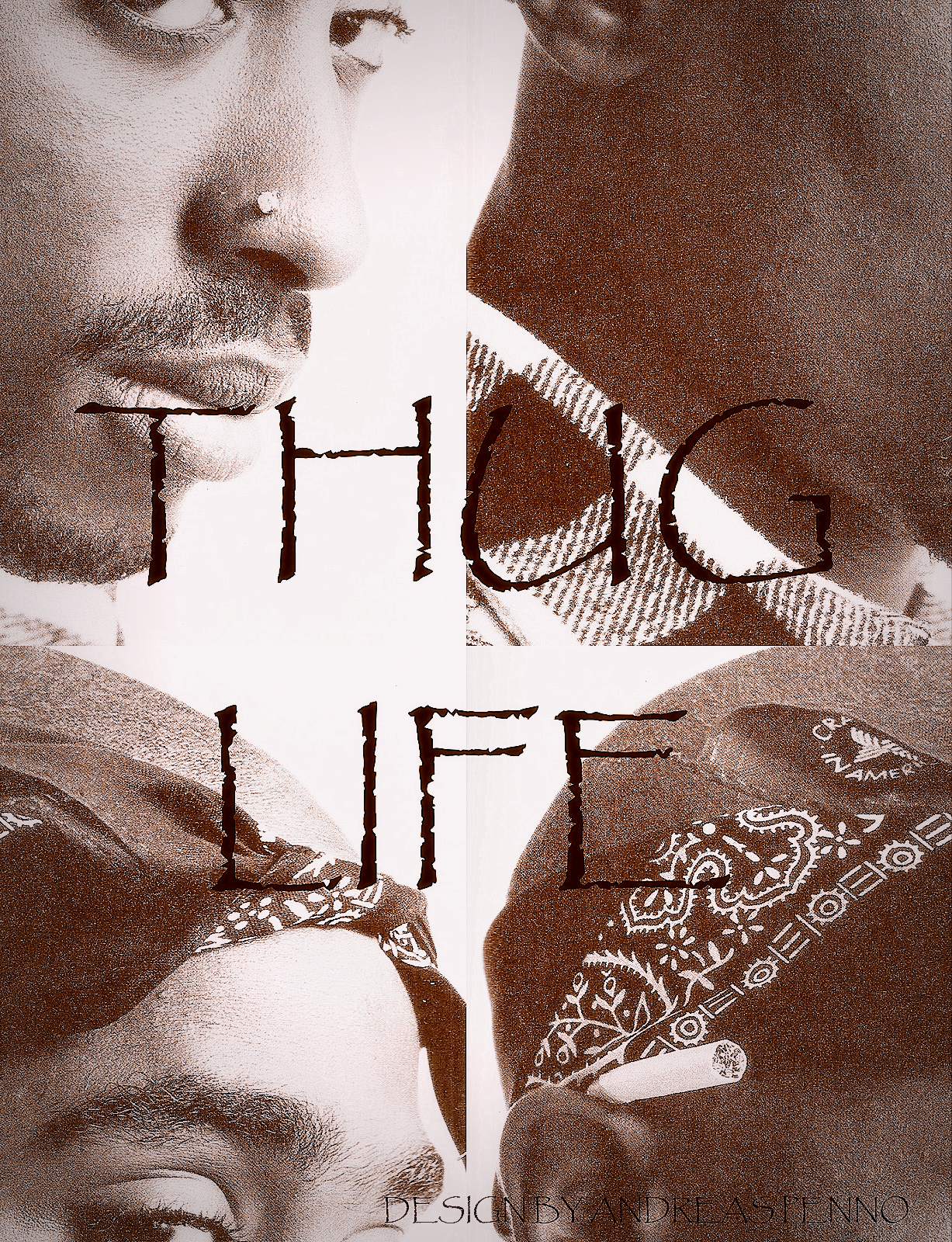

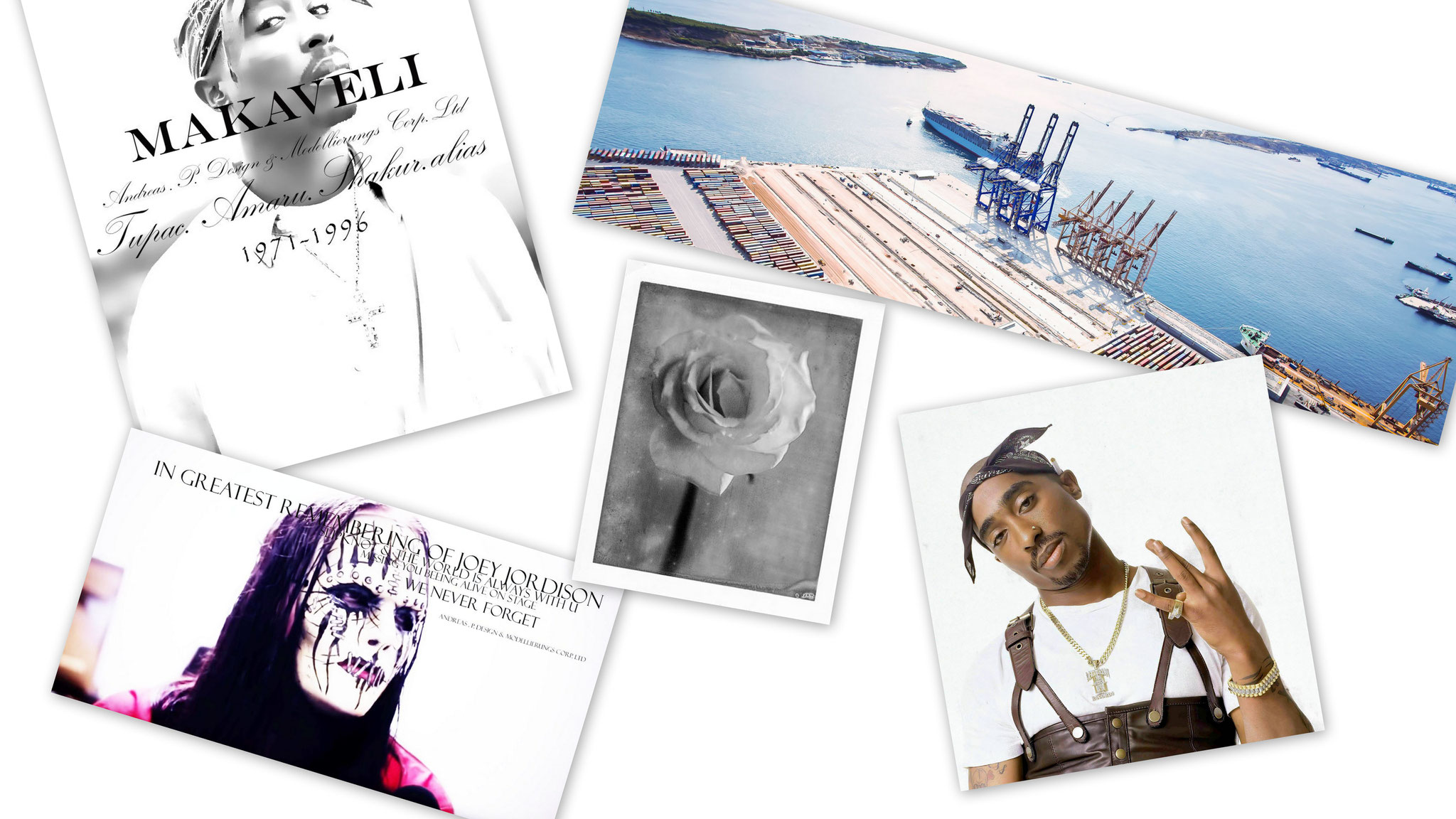

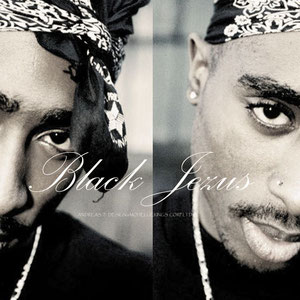

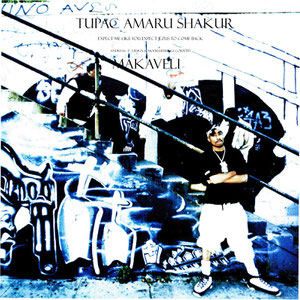

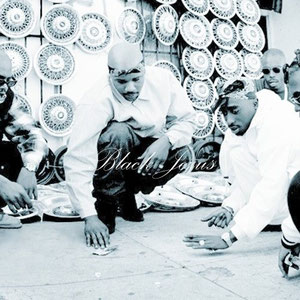

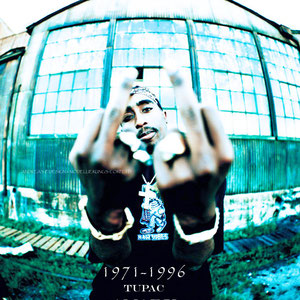

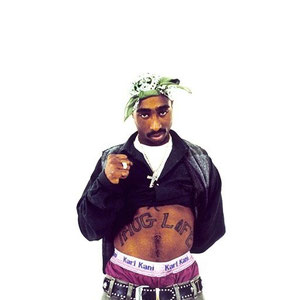

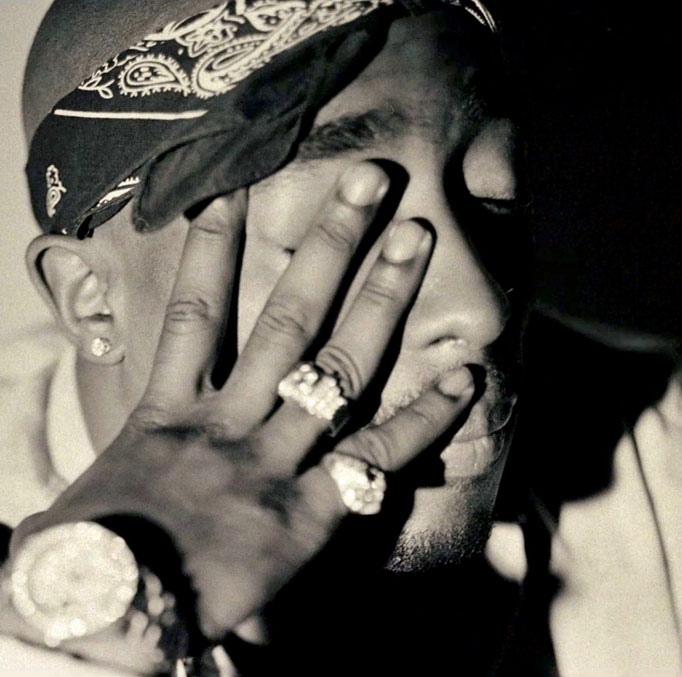

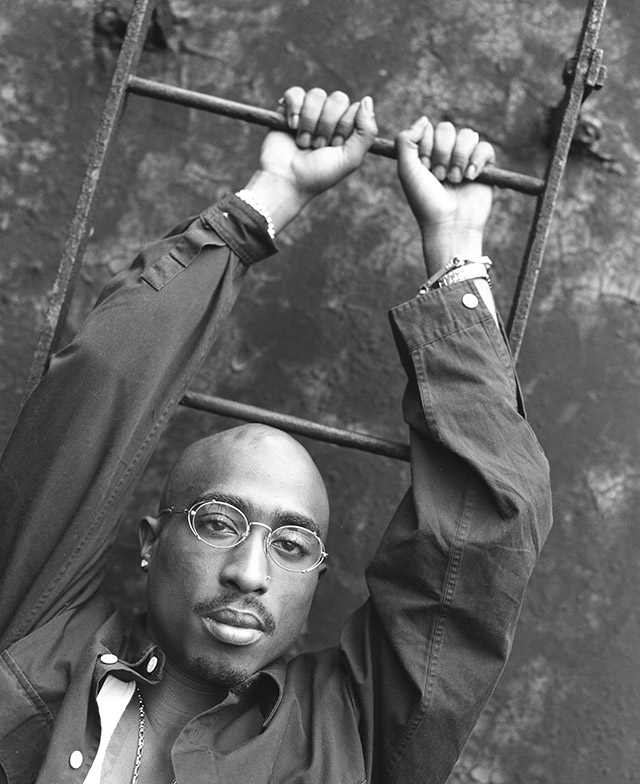

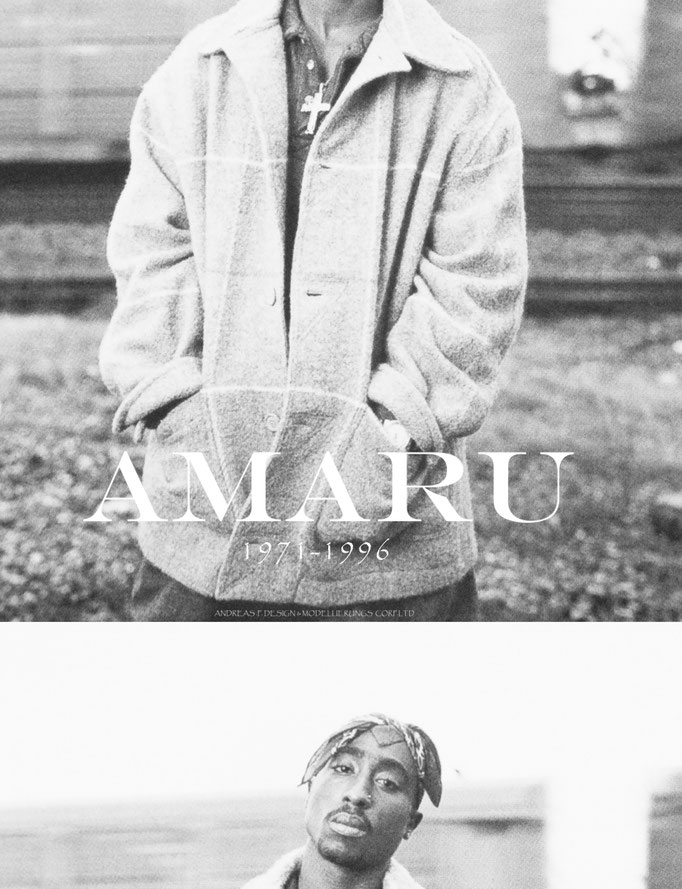

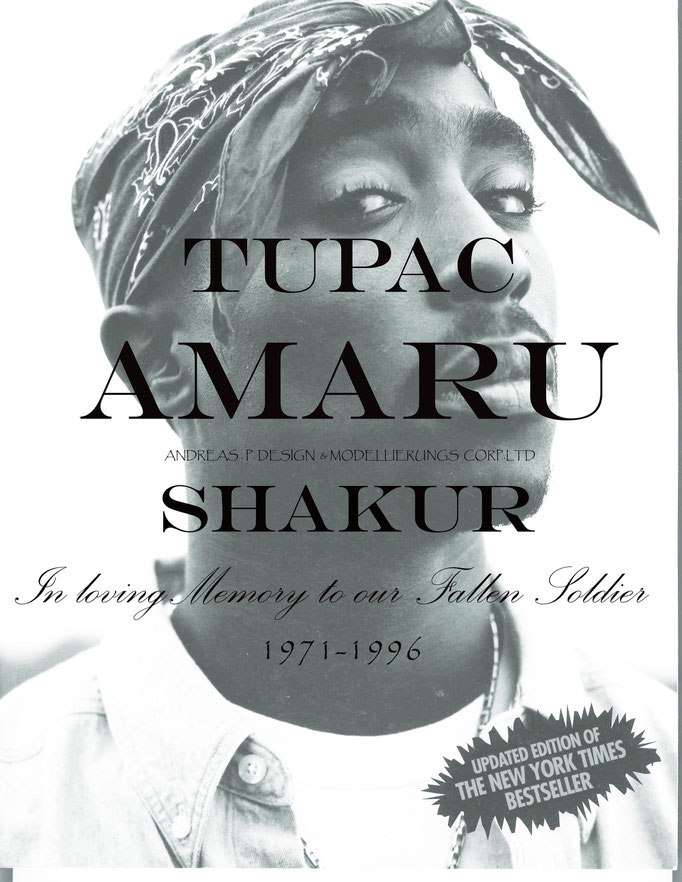

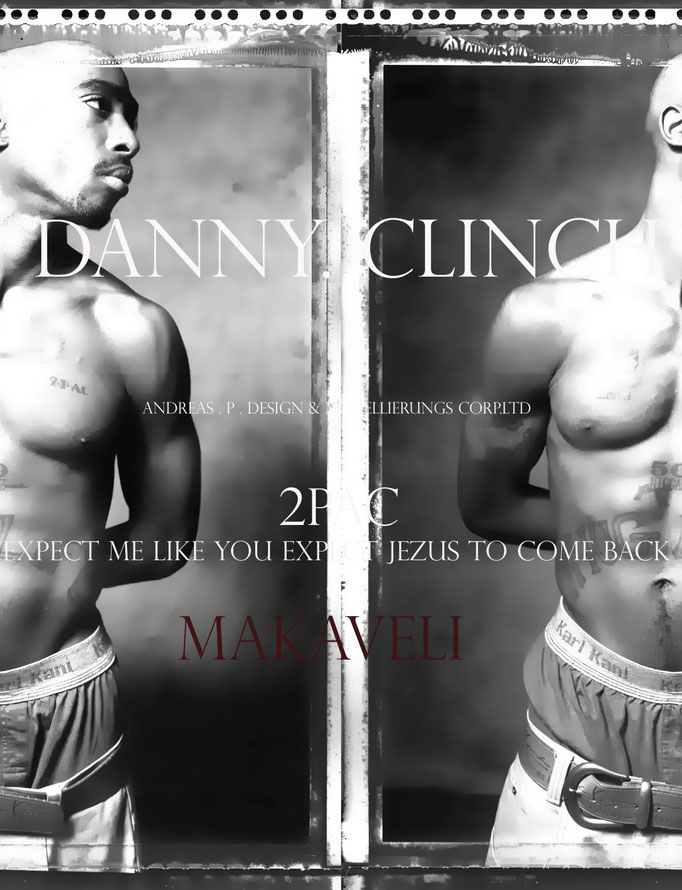

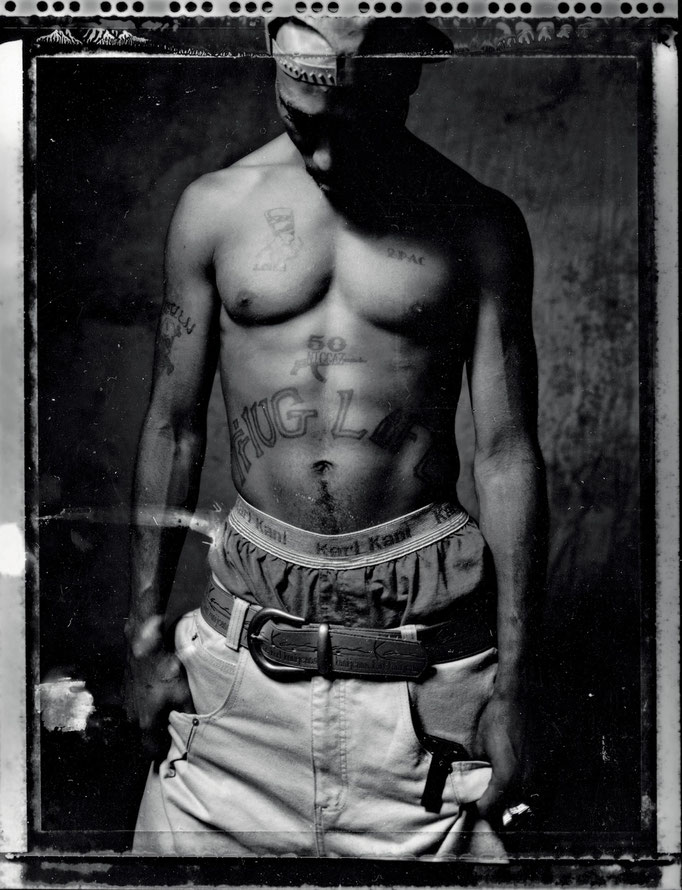

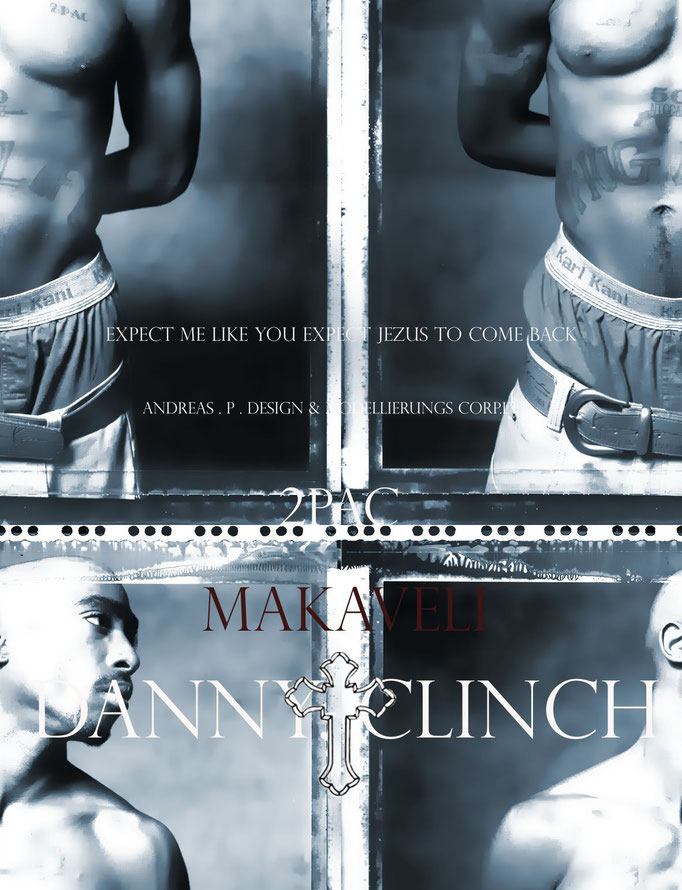

- Black Jesuz / Makaveli / Photography

- Jean Francois Richet

- Lyrics / Composition / World Log

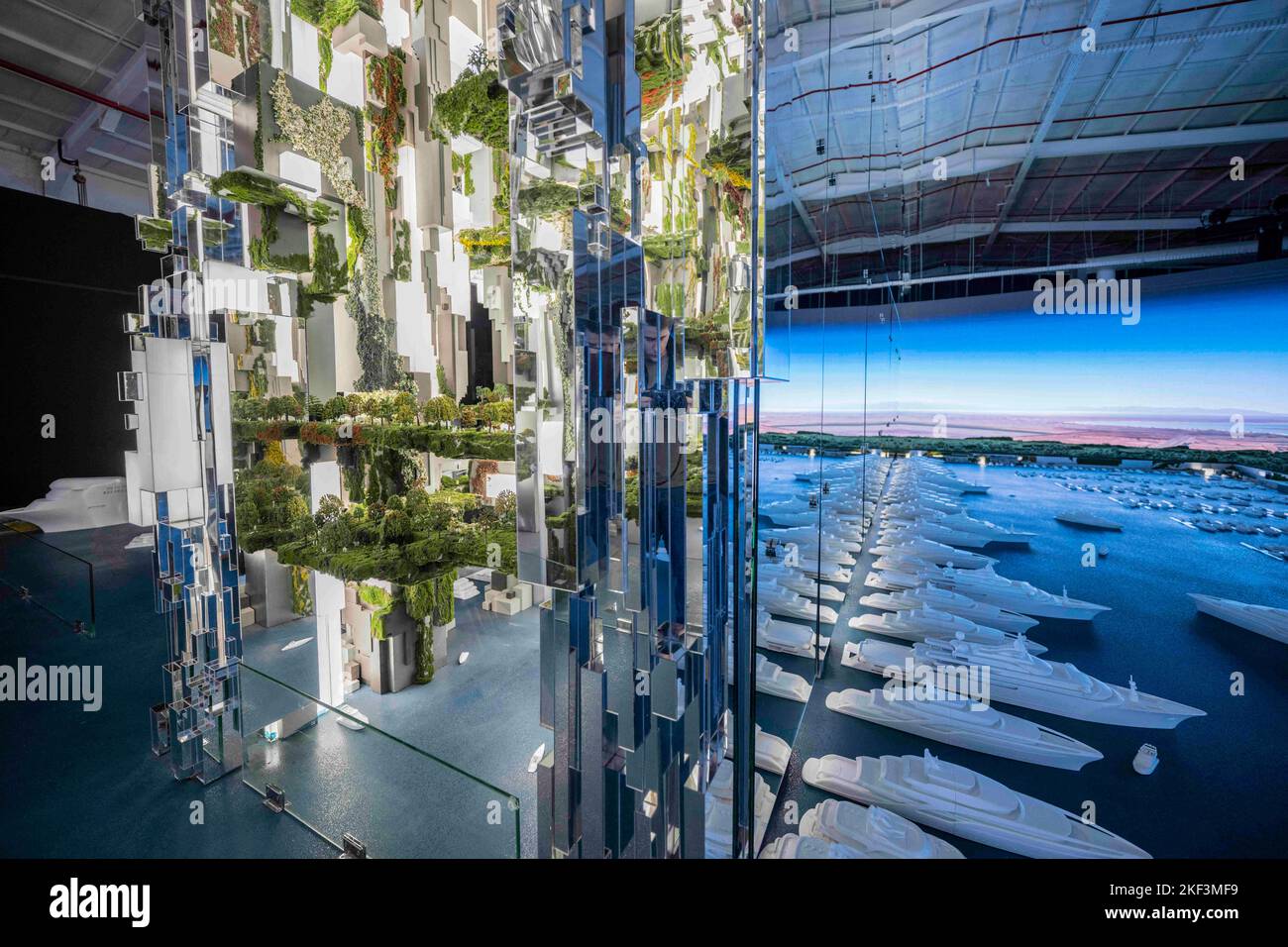

- Andreas . P . Design & Modellierungs Corp. LTD

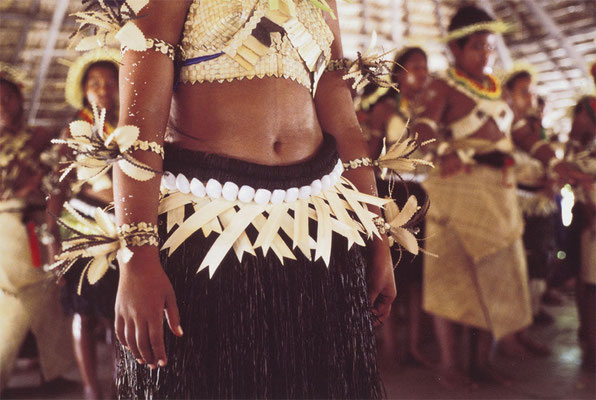

- World / Transcontinental Art / Works / Creation / Culture

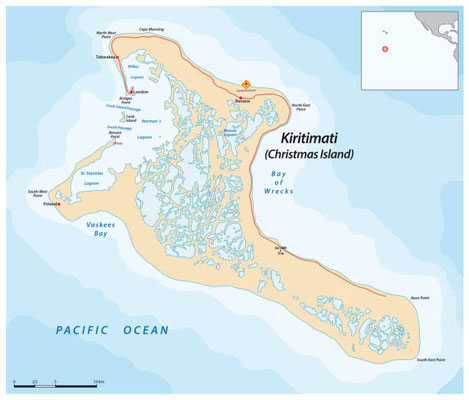

- Coral Reefs / Ocean / Geoecology / Green Environment / Nature

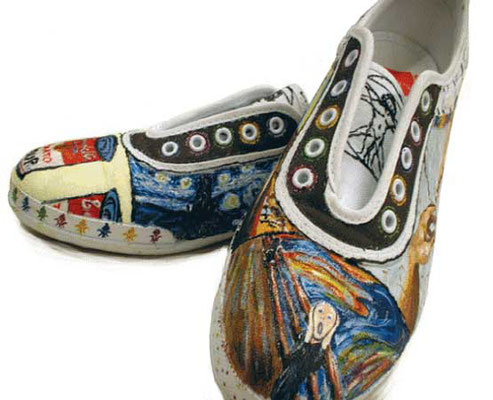

- Fashion / Mode / Vogue

- Finance

- Modellierung & Design 1

- PDF / Portable Document Formats / Protocolations

- Slipknot

- Images / High DPI

- Photography From Me

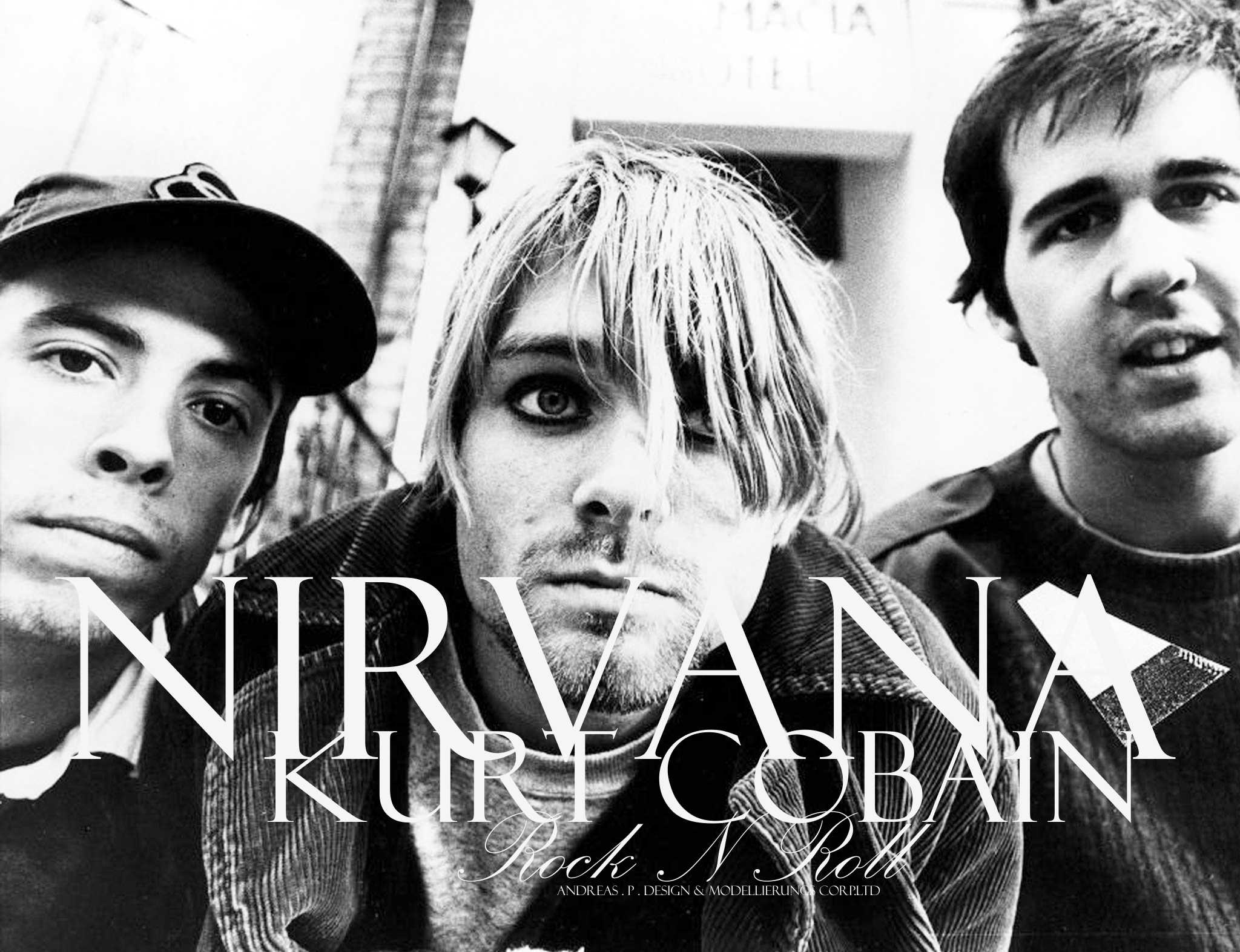

- Kurt Cobain

- Establishment / Industry & Corporation Language

- John F. Kennedy / Documentary / US / Archive

- Justice & Law Terms / Bloomberg / Different Resources from World / Journalism

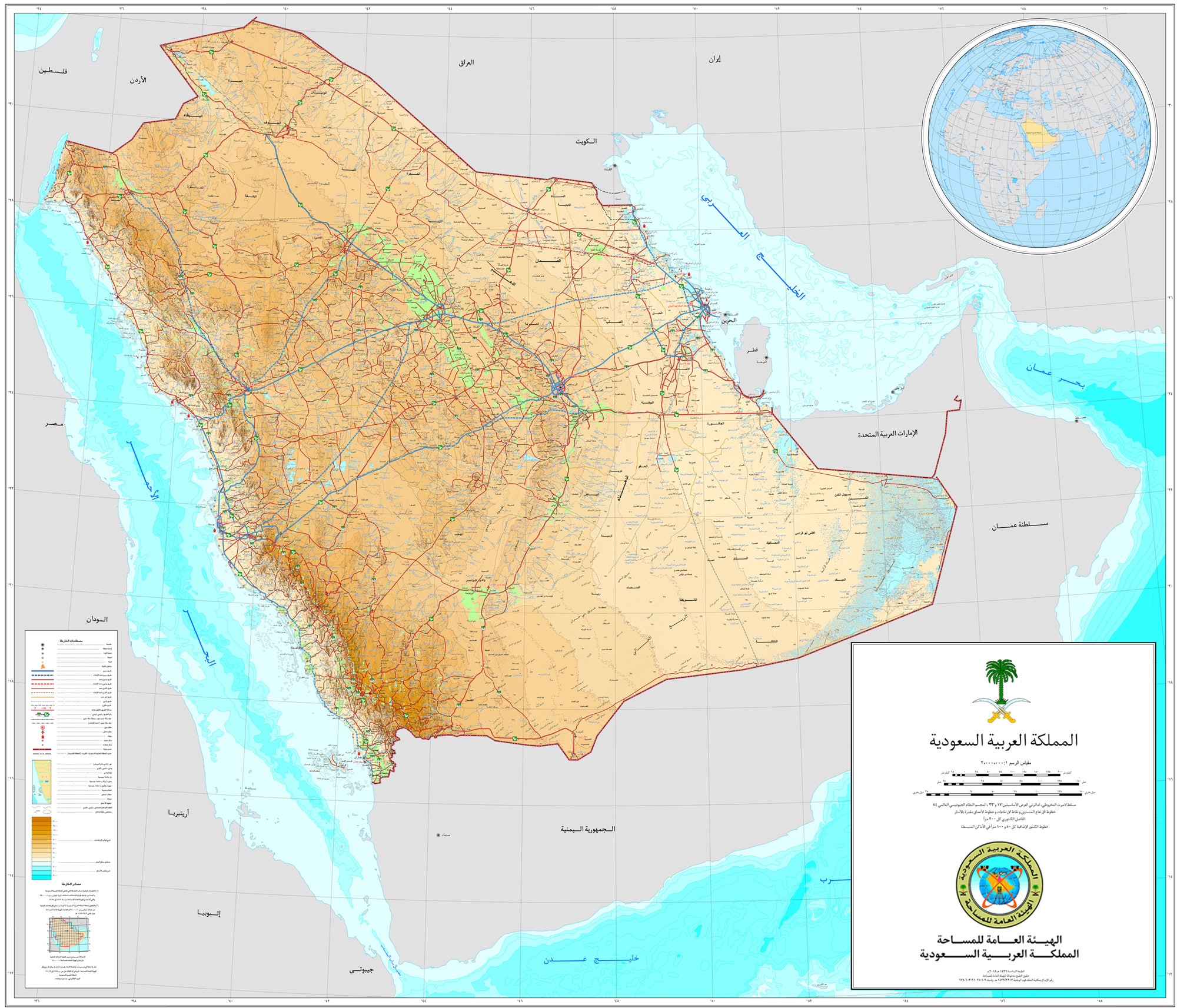

- Medicine / Development / Technology / Economically Intelligent Future / Silk Road / ( China )

- Gangs of New York

- Portable Document Formats / Protocolations / Diversification

- Modellierung & Design 3

- World Economic Model

- M & D 4

- Modellierung & Design 5

- World ( ISS ) Intergalactic Space Exploring ( Universe ) System (A.P.P)

- Germany Native ( DE ) Blog Comprehensive

- ( World ) Active Grand Colosseum ( Sports ) Initiative

- Ideas Commission / World Statement / Archive / Sourcing

- PDF / Diversification / Formats - No.3

- United States of America ( USA ) World Affairs

- World Economic Model 2 ( Flexible Growth Budgeting ) News

- ( M & D ) 6

- Modellierung & Design 7

- ( M & D ) 8 / Multiplex Blogspot

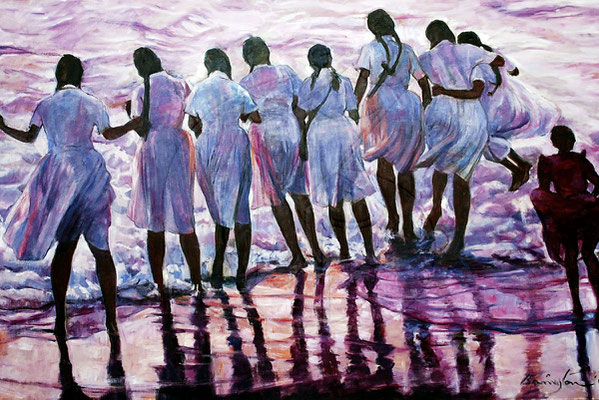

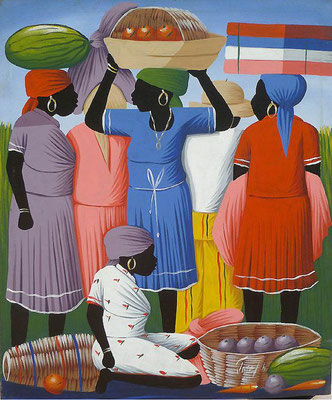

World Arts & Works / Workshop /Transcontinental ( Representation )

World Talented Arts Represented & Opportunities and An Exhibition of Different Creative Arts of North America & Humanity / Paintings / Workshop / Platform

/ Multiplex Mix-Up / Andreas . P . Design & Modellierungs Corp.LTD / Today's Arts News 27.05.2025 AD n.Chr World

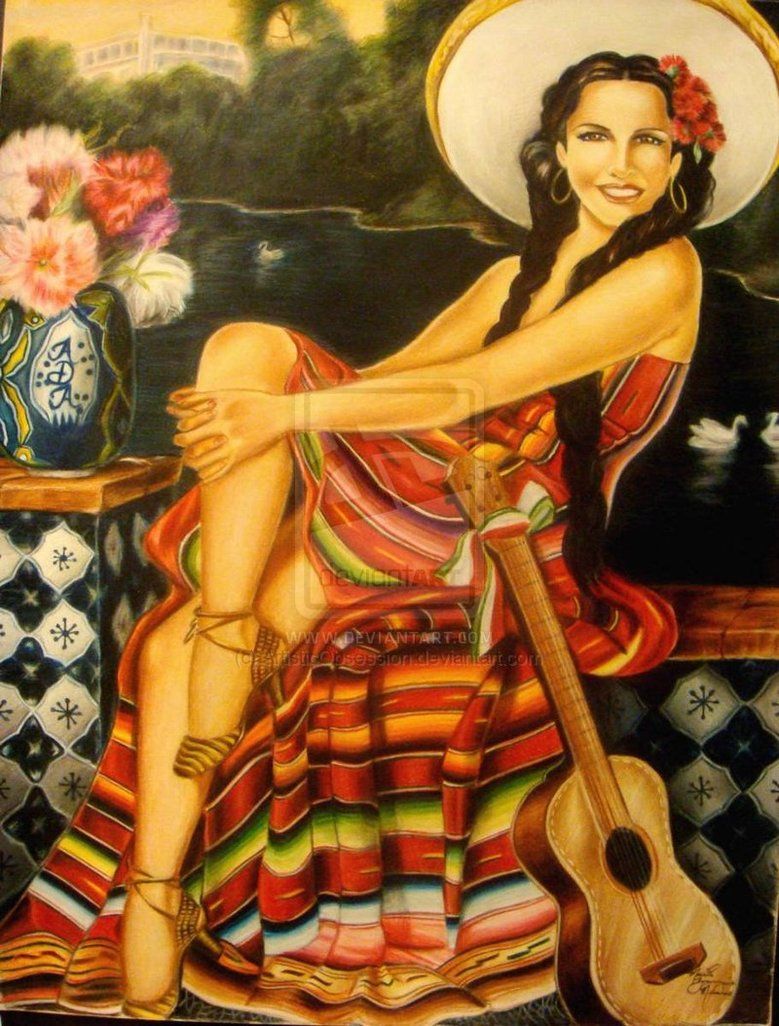

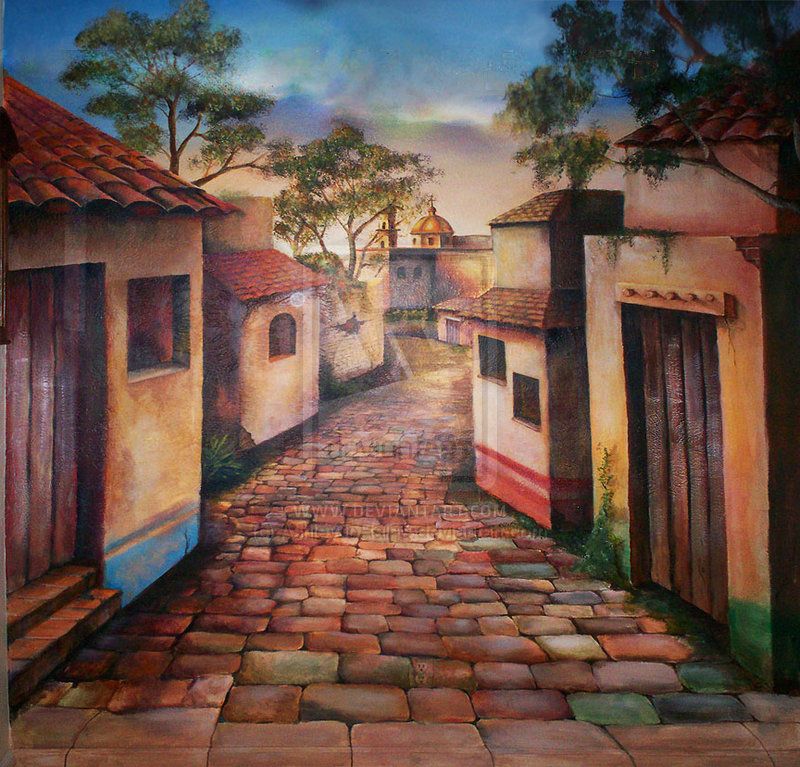

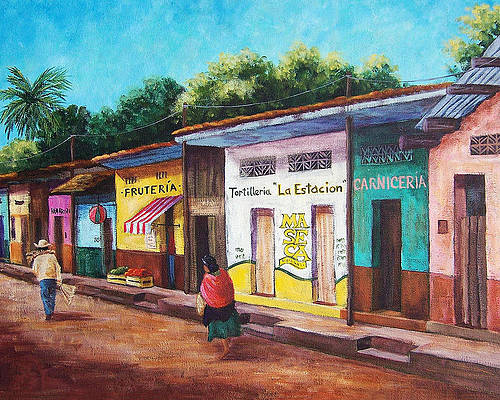

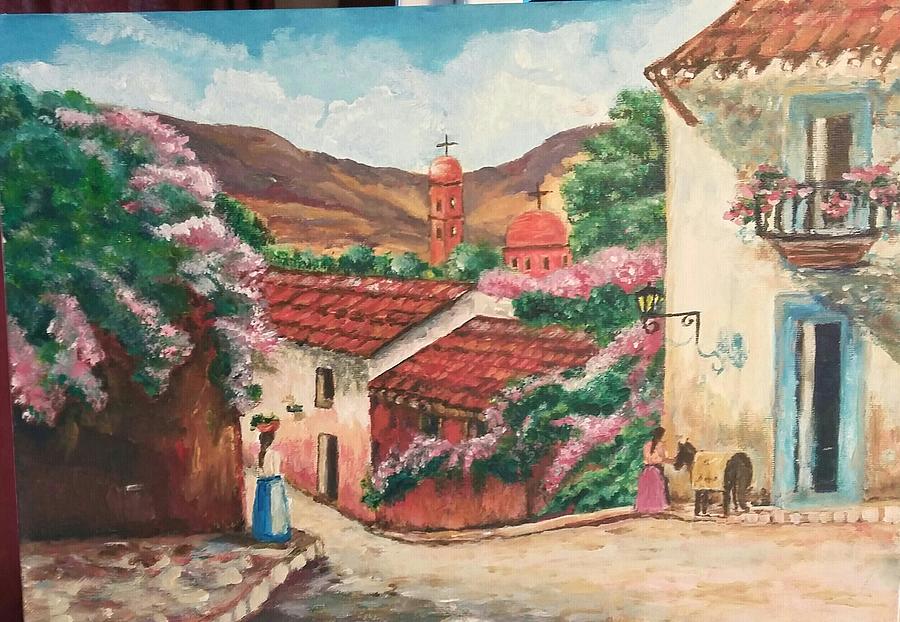

Source Street-Fame.com / Resourcing about the Hispanic American Painter & Artist / One Of Most Notorious Colorists & Artists in History of the USA

Artist Adán Hernandez‘s work was collected by Hollywood celebs, including the likes of Cheech Marin and the one and only Helen Mirren. Still, most recognized his artwork more likely from the paintings he created for the 1993 movie “Blood In Blood Out“. Before “Blood In Blood Out,” Hernandez was a down on his luck artist. After the film came out, the monetary value of his work jumped, & 2 of his paintings were first bought by the Metropolitan Museum of Art for its collection. One of his art pieces from the film is in the San Antonio Museum of Art collection.“All my dreams came true in an avalanche,” he mentioned in the interview with video producer Dan Segovia submitted last year to Chased By Hounds, a Facebook fan page dedicated to the movie. Marin published a picture of the 2 of them on Instagram Monday, writing, “There is no purer voice from the barrio than Adán Hernandez. He was the artistic soul of Chicano noir.” Some of Hernandez’s work was included in”Chicano Visions,” a touring exhibition drawn from Marin’s collection that started at the San Antonio Museum of Art in 2002. As news of the artist’s death reached Hollywood, his family received condolence calls from some people who worked on “Blood In Blood Out,” his brother Armando mentioned, including director Taylor Hackford & costar Benjamin Bratt.

The 1993 film follows three youthful gang members in East Los Angeles whose lives abide by divergent paths as adults– one goes to prison (Damian Chapa), one becomes a cop (Bratt) & one becomes an artist (Jesse Borrego).HERNANDEZ WAS HIRED FOR THE JOB AFTER A PRODUCTION DESIGNER HAPPENED TO SEE SOME OF HIS WORK IN A SAN ANTONIO GALLERY WINDOW.

Originally, the team had considered shooting the film at this said gallery. Hackford asked Hernandez to make more than thirty paintings ascribed to Borrego’s character. He regularly made a painting a day to fulfill the tight deadline. In an interview, he recalled that he was working so fast & so long that his hands were cramped and his vision was impaired. In addition to providing the paintings for the movie, ” he appeared in a small scene. And then he taught Borrego how to mix paint & how to hold a paintbrush. Borrego, a fellow San Antonian, also used a great deal of time in Hernandez’s studio, watching him work & folding details from these hours Into his performance. They became intimate friends. And they had expected to one day open up a Chicano art museum on the West Side. Borrego, to this day, expects to make that happen, with pieces by Hernandez as a centerpiece.

“But it’s going to be sad, looking at all types of his work that’s going to be past work, not the stuff he still wanted to paint,” he mentioned. “His work will live on after him, & I think it’s going to be remarkable for art history one day. Independent curator Joseph Bravo, which was well-acquainted with Hernandez for more than 20 years, sees the late artist as one among the biggies of all Chicano art, putting him on the same degree as Mel Casas, Jesse Treviño, and César Martínez.

The movie is what catapulted him into that tier, Bravo stated.

“Those paintings were tremendously important in the Chicano imagination because where were you going to see paintings in the barrio? There were no museums, no retail art galleries,” he mentioned.

The film relayed the message that being an artist is a possibility for Latinos, ” he mentioned. And Hernandez’s paintings for the film captured optimistic images.

“Yes, they dressed the way they dressed; they looked like cholos,” Bravo stated. “But he humanized them, and they weren’t simply caricatures any longer.”

Later, Hernandez’s work shifted to Chicano noir, darker, heavier, more disturbing paintings. In a similar vein, he also composed and illustrated”Los Vryosos: A Tale From the Varrio,” a crime novel published in 2006. César Martinez, who resided right next door to Hernandez, stated he was intrigued with his work the 1st time he saw it, and the two artists broke a friendship.“Like me, he tended to be very private & needed privacy to do his work, but was affable in-person & very easy to hang out with,” Martínez stated via email. “His passing leaves a void.”

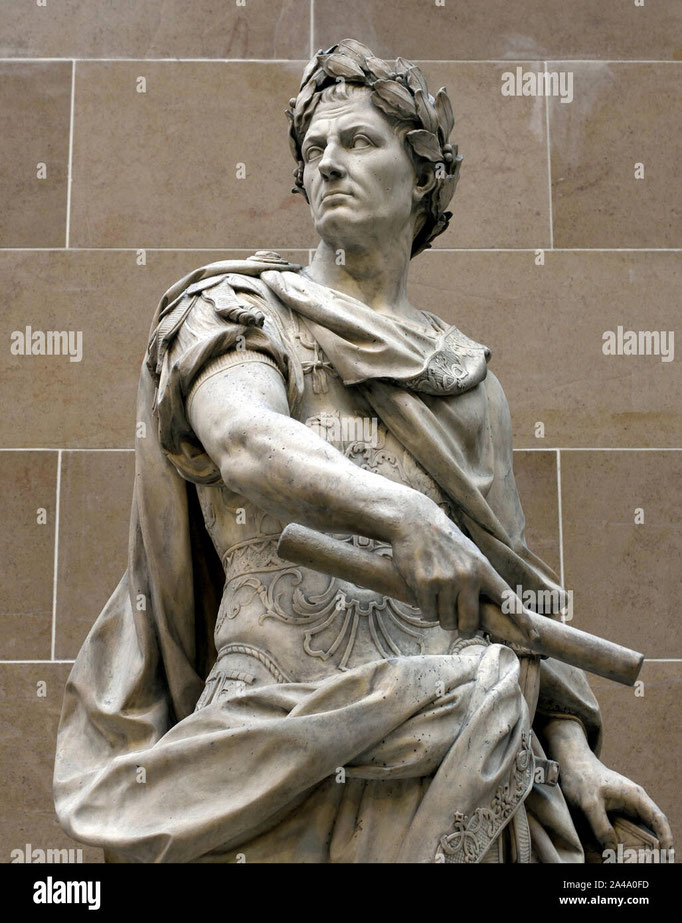

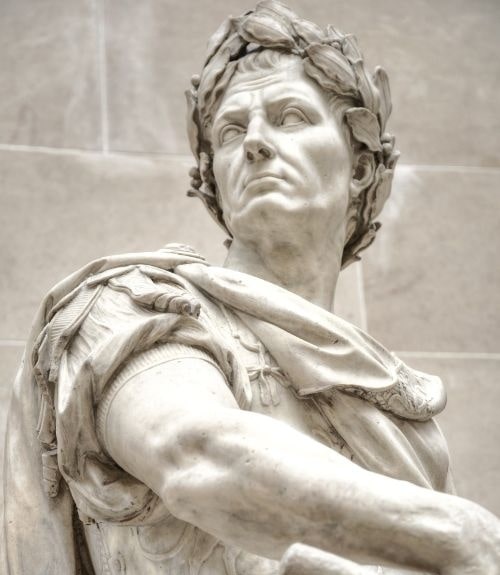

Hernandez used the earlier years of his life in Robstown, by which he & his family worked in the cotton fields. When he was 9, they proceeded to San Antonio’s West Side. He discovered an affinity for art at Edgewood High School and studied at San Antonio School for a while. However, he was put off with the emphasis on classical Greco-Roman forms — he didn’t see much of a link in the middle of that and the Chicano experiences that he wanted to capture in his work — so he fell out. After that, he was largely self-taught. “My brother & I grew up idolizing 3 San Antonio artists as kids: César Martínez, Jesse Treviño, & Adán Hernandez, the holy trinity of San Anto Art in the 1980s & early’90s,” Rigoberto Luna, an artist & curator of both Presa House Gallery, composed in an email. “I was lucky to meet Adán through the late Manuel Castillo. My brother and my first art gallery show were at Adán’s gallery El Otro Ojo. He was an original, an innovator, & a torchbearer for Chicano art.”

Painter Gerardo Quetzatl Garcia remembered introducing himself as a teen to Hernandez, worried about meeting the artist who had made the “Blood In Blood Out” paintings. “Never one to belittle or condescend, his huge skill seemed to have a small influence on how he treated others, and I feel that’s one of the many things that will be missed by his passing,” Garcia stated. Hernandez inspired Eddie Salinas, his second cousin, to go after a music career.

“He was an amazing artist and activist for the Chicano culture, & he’s influenced thousands, if not millions of Latino artists, myself being living proof that his art and stance in the culture has inspired many to strive for life outside of the barrios that a lot of us struggle to get out of,” Salinas stated.

“He opened the door & showed that it’s possible to pursue passions, especially within the art realm.” And then he was all the time game to talk about “Blood In Blood Out.” When Segovia reached out to him via Facebook about five years ago and asked if he can interview him about the movie, Hernandez responded right away, inviting him to film their chat in his studio. “That isn’t an uncommon story,” Segovia mentioned. “If you talk to almost anyone who was a big fan of his work, he extended an invite. That’s the kind of male he was. He was very open to the community, very willing to share his story.” Segovia stated many opinions on the “Chased By Hounds” page have to do with Hernandez’s work. “It’s wild to see others tattooing his art on their body,” he mentioned. “That’s what those images mean to people.” As important as the film is to many, including Borrego, Hernandez’s influence goes beyond it, the actor stated. “His work is very remarkable & prolific beyond the cult status of ‘Blood In Blood Out,”’ he stated. “We lost a good one.” He is survived by his kids, Adam Hernandez, James Hernandez, Cory Hernandez, Italia Lane and Clayton Hernandez, & from his siblings, Gloria Treviño, Robert Hernandez, David Hernandez, Ruben Hernandez, Armando Hernandez & Bert Hernandez

Chicano Arts in World / American & Spanish ( Chicano Movement ) / History / Society & Mexico / North America / Creativity / America Works / Arts / Comprehensive Portrayal

The Chicano art movement refers to the ground-breaking Mexican-American art movement in which artists developed an artistic identity, heavily influenced by the Chicano movement of the 1960s. Chicano artists aimed to form their own collective identity in the art world, an identity that promoted pride, affirmation, and a rejection of racial stereotypes. The most well-known and famous Chicano artists include Carlos Almaraz, Chaz Bojórquez, Richard Duardo, Yreina Cervántez, and Magú. Chicano artists developed their works to exist as a form of a community-based representation of life in the barrio, but it also acted as a form of activism for social issues faced by Latin-American people in the United States.

The Chicano art movement began in the late 1960s and early 1970s, alongside the growth of the Chicano movement, or El Movimiento, and was created and defined by Mexican people, or people of Mexican descent living in the United States. The term “Chicano” is used interchangeably with “Mexican-American”, emerging from the youth who rejected assimilation to the Euro-Centric American culture. The term was widely used in the 1960s and 1970s and became associated with indigenous pride, culture affirmation, ethnic solidarity, and political empowerment. The Chicano art movement involved Chicano artists forming and establishing a specific and unique artistic identity, that diverted from the mainstream United States art forms. As the movement was meant to represent a rejection of the White-American culture and its forms of art, the Chicano movement aimed to form and develop a collective identity that distinguished itself as Mexican-American. Chicano muralists and Chicano painters drew their inspiration from Mexican murals and Pre-Columbian Art. Pre-Columbian art refers to works made by the Aztec, Inca, Mayan, and Native Mexican people.

These communities, all native to Latin America or South America, were heavily disrupted by the colonization by the Spanish conquistadors. The Chicano movement, and by extension, the Chicano art movement aimed to reject the dominant White American culture, which their ancestors were unable to do when the Spanish invaded. Chicano artists developed their work as an expression of their experiences and culture. Often, Chicano art drawings feature the subject of “rasquachismo”, which refers to the Spanish word, “rasquache”, which means “poor”. Rasquachismo refers to the cultural attitude to always be hard-working and resourceful, getting by with the few resources they tend to have in a society dominated by wealthy White Americans. In other words, the Chicano art movement was meant to be a form of protest, with the artwork often being very direct and vibrant. Chicano mural paintings not only promoted community in their subject matter but often involved community members in their creation; discussing and formulating what they wanted to depict based on their cultural history and struggles. These murals were often painted by self-taught artists, which again shows the movement’s value for resourcefulness. These murals were usually painted on public walls, where entire communities would be able to see by walking or driving by. The public nature of this art form emphasized histories that were often overshadowed by the White-American narrative, which tended to present historical events in a pro-European light. This public nature allowed for audiences to be politicized and mobilized without expecting them to go into an art gallery or museum. Besides murals, Chicano artists also used silkscreen creations, which allowed for the production of posters and printed images, that could be distributed in large numbers, spreading the political and social aspect of the Chicano movement. The subject matter of Chicano art commonly features imagery relating to issues of immigration and displacement, issues that the Latin communities of the United States often dealt with. Mexicans often struggle with immigration to the United States and native Mexicans and South Americans were being displaced by Spanish and Portuguese colonization.

Chicano Collection / Artists from North America & Mexican American Painters, Artists / Creativity / Exhibitions / Murals / Streets / Arts / Graffiti / A.P. P / Curated / Images

Chicano Art Movement / North America / Mexican American Individuals Creating Art in Hollywood / About the Chicanos Painting Products of Glamour & Flavour With Brushes & Color / Graffiti & Murals New York

The Chicano Art Movement represents groundbreaking movements by Mexican-American artists to establish a unique artistic identity in the United States. Much of the art and the artists creating Chicano Art were heavily influenced by Chicano Movement (El Movimiento) which began in the 1960s.

Chicano art was influenced by post-Mexican Revolution ideologies, pre-Columbian art, European painting techniques and Mexican-American social, political and cultural issues.[1] The movement worked to resist and challenge dominant social norms and stereotypes for cultural autonomy and self-determination. Some issues the movement focused on were awareness of collective history and culture, restoration of land grants, and equal opportunity for social mobility. Women used ideologies from the feminist movement to highlight the struggles of women within the Chicano art movement.

Throughout the movement and beyond, Chicanos have used art to express their cultural values, as protest or for aesthetic value. The art has evolved over time to not only illustrate current struggles and social issues, but also to continue to inform Chicano youth and unify around their culture and histories. Chicano art is not just Mexican-American artwork: it is a public forum that emphasizes otherwise "invisible" histories and people in a unique form of American

Beginning in the early 1960s, the Chicano Movement, was a sociopolitical movement by Mexican-Americans organizing into a unified voice to create change for their people. The Chicano Movement was focused on a fight for civil and political rights of its people, and sought to bring attention to their struggles for equality across southwest America and expand throughout the United States.[3] The Chicano movement was concerned with addressing police brutality, civil rights violations, lack of social services for Mexican-Americans, the Vietnam War, educational issues and other social issues.[3]

The Chicano Movement included all Mexican-Americans of every age, which provided for a minority civil rights movement that would not only represent generational concerns, but sought to use symbols that embodied their past and ongoing struggles. Young artists formed collectives, like Asco in Los Angeles during the 1970s, which was made up of students who were just out of high school.[4]

The Chicano movement was based around the community, an effort to unify the group and keep their community central to social progression, so they too could follow in the foot steps of others and achieve equality. From the beginning Chicanos have struggled to affirm their place in American society through their fight for communal land grants given to them by the Mexican government were not being honored by the U.S. government after the U.S. acquired the land from Mexico. The solidification of the Chicano/a struggles for equality into the Chicano Movement came post World War II, when discrimination towards returning Mexican-American servicemen was being questioned, for the most part these were usually instances of racial segregation/discrimination that spanned from simple dining issues to the burial rights of returning deceased servicemen.

The formation of the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), co-founded by César Chávez, Dolores Huerta, and Gil Padilla, sought to unionize Mexican-American labor forces to fight for improved wages/working conditions through such forms as strikes, marches, and boycotts was a notable spike in the national awareness of El Movimiento.[3] Using symbols, such as the black eagle and creating unique poster and union art, helped raise awareness of the social issues NFWA faced, even while the workers themselves were largely invisible.[2]

Aztlán is also another consistent symbol used by the Chicano Movement, the term unified the Mexican Americans under a term of inheritance of land and culture. Along with this common rhetoric of land claims and civil rights, an alternative to the peaceful protesting of César Chávez, Reies Lopez Tijerina attempted to resolve the issues of communal land grants in New Mexico through the creation of Alianza Federal de Mercedes and eventually resulting in attempts to secede from the Union and form their own territory, Republic of Chama.

The union then brought in thousands more lettuce and vegetable pickers in the Salinas Chicano Movement art developed out of necessity for a visual representation of the self perceived sociopolitical injustice that the movement was seeking out to change. As in any movement there is a need for signage that brings awareness to the issues at hand, starting with murals. Murals represented the main form of activism in Mexico prior to the Chicano Movement taking place in the United States. The murals depicted the lives of native Mexicans and their struggles against the oppression of the United States, as well as, native problems to Mexico's poverty and farming industry. Many of the images and symbols embodied in these classic Mexican graffiti murals were later adopted by the Chicano Movement to reaffirm and unify their collective under a specific light of activism.

Chicano art as activism

“El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán understood art as a vehicle of the movement and of revolutionary culture”.[5] Although the Chicano movement dissolved, Chicano art continued as an activist endeavor, challenging the social constructions of racial/ethnic discrimination, citizenship and nationality, labor exploitation, and traditional gender roles in effort to create social change. As Fields further explains, “Linked to its constitutive phased with the Chicano movement, or Movimiento, of the 1960s and 1970s, Chicano/a art articulated and mirrored a broad range of themes that had social and political significance, particularly with respect to cultural affirmation”.[6] Activism often took form in representing alternative narratives to the dominant through the development of historical consciousness, illustrations of injustices and indignities faced by Mexican-American communities, and development of a sense of belonging of Chicanos within the United States. Chicano art in its activist endeavors has become a form of popular education, of the people and by the people, in its ability to create a dialogue about these issues while empowering Chicanos to construct their own solutions.

Geography, immigration and displacement are a common themes in Chicano art.[7] Taking an activist approach, artists illustrate the historical presence of Mexicans and indigenous peoples in the Southwest, human rights abuses of undocumented immigrants, racial profiling, and the militarization of the border. “Many Chicano artists have focused on the dangers of the border, often using barbed wire as a direct metaphorical representation of the painful and contradictory experiences of Chicanos caught between two cultures”.[8] Art provides a venue to challenge these xenophobic stereotypes about Mexican-Americans and bring awareness to our broken immigration law and enforcement system, while simultaneously politicizing and mobilizing its audience to take action. Another common theme is the labor exploitation in agricultural, domestic work, and service industry jobs, particularly of the undocumented. Drawing from the Chicano movement, activists sought art as a tool to support social justice campaigns and voice realities of dangerous working conditions, lack of worker's rights, truths about their role in the U.S. job market, and the exploitation of undocumented workers. Using the United Farm Workers campaign as a guideline, Chicano artists put stronger emphasis on working-class struggles as both a labor and civil rights issue for many Chicanos and recognized the importance of developing strong symbols that represented the movement's efforts, such as the eagle flag of the UFW, now a prominent symbol of La Raza.[9] Often through the distribution of silk-screen posters, made on large scales, artists are able to politicize their community and make a call to mobilize in effort to stop immigration raids in the workplace and boycott exploitative and oppressive corporations, while exemplifying dignity and visibility to an often invisible working population.

The Chicano People's Park (Chicano Park) in San Diego highlights the importance of activism to Chicano art. For many years, Barrio Logan Heights petitioned for a park to be built in their community, but were ignored.[10] In the early 1960s, the city instead tore down large sections of the barrio to construct an intersection for the Interstate 5 freeway and on-ramp for the Coronado Bridge which bisected their community and displaced 5000 residents.[10] In response, “on April 22, 1970, the community mobilized by occupying the land under the bridge and forming human chains to halt the bulldozers” who were working to turn the area into a parking lot. The park was occupied for twelve days, during which people worked the land, planting flowers and trees and artists, like Victor Ochoa, helped paint murals on the concrete walls.[10] Now this park is full of murals and most of them refer to the history of the Chicanos. Some of them include Cesar Chavez, La Virgen de Guadalupe and many others.[11] Residents raised the Chicano flag on a nearby telephone pole and began to work the land themselves, planting flowers and “re-creating and re-imagining dominant urban space as community-enabling place”.[12] After extensive negotiations, the city finally agreed to the development of a community park in their reclamation of their territory.[10] From here, Salvador Torres, a key activist for the Chicano Park, developed the Chicano Park Monumental Mural Program, encouraging community members and artists to paint murals on the underpass of the bridge, transforming the space blight to beauty and community empowerment. The imagery of the murals articulated their cultural and historical identities through their connections to their indigenous Aztec heritage, religious icons, revolutionary leaders, and current life in the barrios and the fields. Some iconography included Quetzalcoatl, Emiliano Zapata, Coatlicue (Aztec Goddess of Earth), undocumented workers, La Virgen de Guadalupe, community members occupying the park, and low-riders.[13] As Berelowitz further explains, “the battle for Chicano Park was a struggle for territory, for representation, for the constitution of an expressive ideological-aesthetic language, for the recreation of a mythic homeland, for a space in which Chicano citizens of this border zone could articulate their experience and their self-understanding”.[12] The significance of the repossession of their territory through the Chicano People's Park is intimately connected to their community's experience, identity, and sense of belonging.

As expressed through the Chicano Peoples’ Park, community-orientation and foundation is another essential element to Chicano art. Murals created by Chicano artists reclaim public spaces, encourage community participation, and aid in neighborhood development and beautification. “In communities of Mexican descent within the United States, the shared social space has often been a public space. Many families have been forced to live their private lives in public because of the lack of adequate housing and recreational areas”.[15] Community-based art has developed into two major mediums – muralism and cultural art centers. Chicano art has drawn much influence from prominent muralists from the Mexican Renaissance, such as Diego Rivera and José Orozco.[16] Chicano art was also influenced by pre-Columbian art, where history and rituals were encoded on the walls of pyramids.[16] Even so, it has distinguished itself from Mexican muralism by keeping production by and for members of the Chicano community, representing alternative histories on the walls of the barrios and other public spaces, rather than sponsorship from the government to be painted in museums or government buildings. In addition, Chicano mural art is not an exhibition of only one person's art, but rather a collaboration among multiple artists and community members, giving the entire community ownership of mural. Its significance lies in its accessibility and inclusivity, painted in public spaces as a form of cultural affirmation and popular education of alternative histories and structural inequalities.[17] The community decides the meaning and content of the work. “In an effort to ensure that the imagery and content accurately reflected the community, Chicano artists often entered into dialogue with community members about their culture and social conditions before developing a concept – even when the mural was to be located in the muralist’s own barrio”.[18] Accessibility not only addresses public availability to the community, but also includes meaningful content, always speaking to the Chicano experience.

Pinches Rinches Series by Natalia Anciso, as seen from Galeria de la Raza's Studio 24, on the corner of 24th and Bryant in the Mission District of San Francisco.

Cultural art centers are another example of community-based Chicano art, developed during the Chicano Movement out of need for alternative structures that support artistic creation, bring the community together, and disseminate information and education about Chicano art. These centers are a valuable tool that encourages community gatherings as a way to share culture, but also to meet, organize and dialogue about happenings in the local Chicano community and society as a whole. “In order to combat this lack of voice, activists decided it was essential to establish cultural, political, and economic control of their communities”.[19] To again ensure accessibility and relevance, cultural art centers were located in their immediate community. These spaces provided Chicanos with an opportunity to reclaim control over how their culture and history is portrayed and interpreted by society as a whole. As Jackson explains, these centers “did not take the public museum as their guide; not only did they lack the money and trained staff, they focused on those subjects denied by the public museum’s homogenized narrative and history of the United States”. An example of a prominent cultural art center is Self-Help Graphics and Art Inc., a hub for silkscreen printmaking, an exhibition location, and space for various types of civic engagement. Beginning in the 1970s, their goal to foster “Chicanismo” by educating, training and empowering young adults has continued to the present day.[21] Self-Help Graphics offered apprenticeship opportunities, work alongside an experienced silkscreen printer, or ‘master printer,’ to develop their own limited-edition silkscreen print. The center also maintained efforts to support the local community by allowing artists to exhibit their own prints and sell them to support themselves financially.[22] As common to successful cultural art centers, Self-Help Graphics supported the development of Chicano art, encouraged community development, and provided an opportunity for empowerment for the Chicano peoples.Other community-based efforts include projects for youth, such as the Diamond Neighborhood murals where Victor Ochoa and Roque Barros helped teach youth to paint in an area that had once been overwhelmed with graffiti. About 150 teenagers attended daily art classes taught by Ochoa and graffiti declined significantly.

World / Globally / European Continent /( EU ) / Germany / Cologne / UTC GMT +2 / 21.04.2024 / 04:18

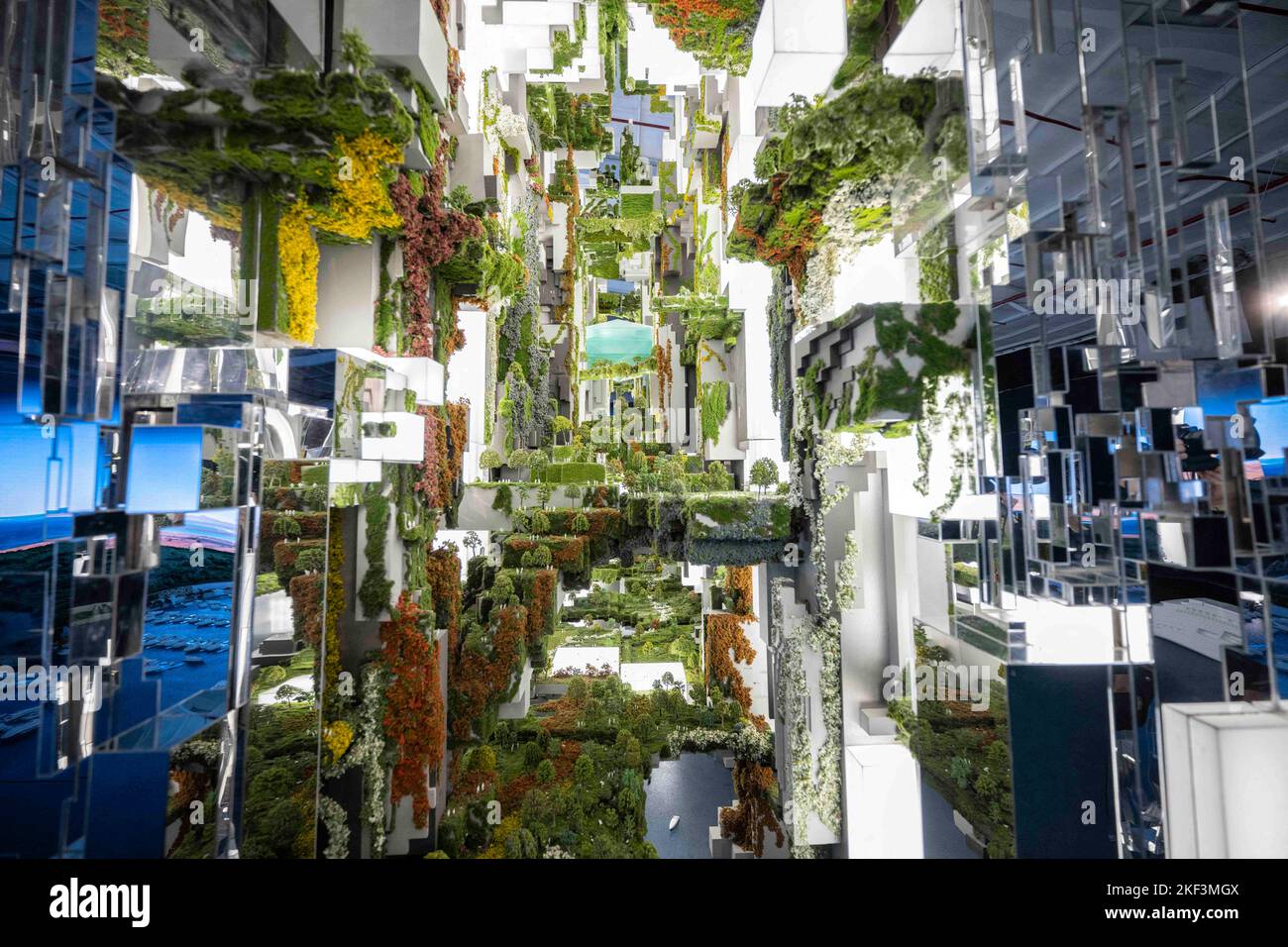

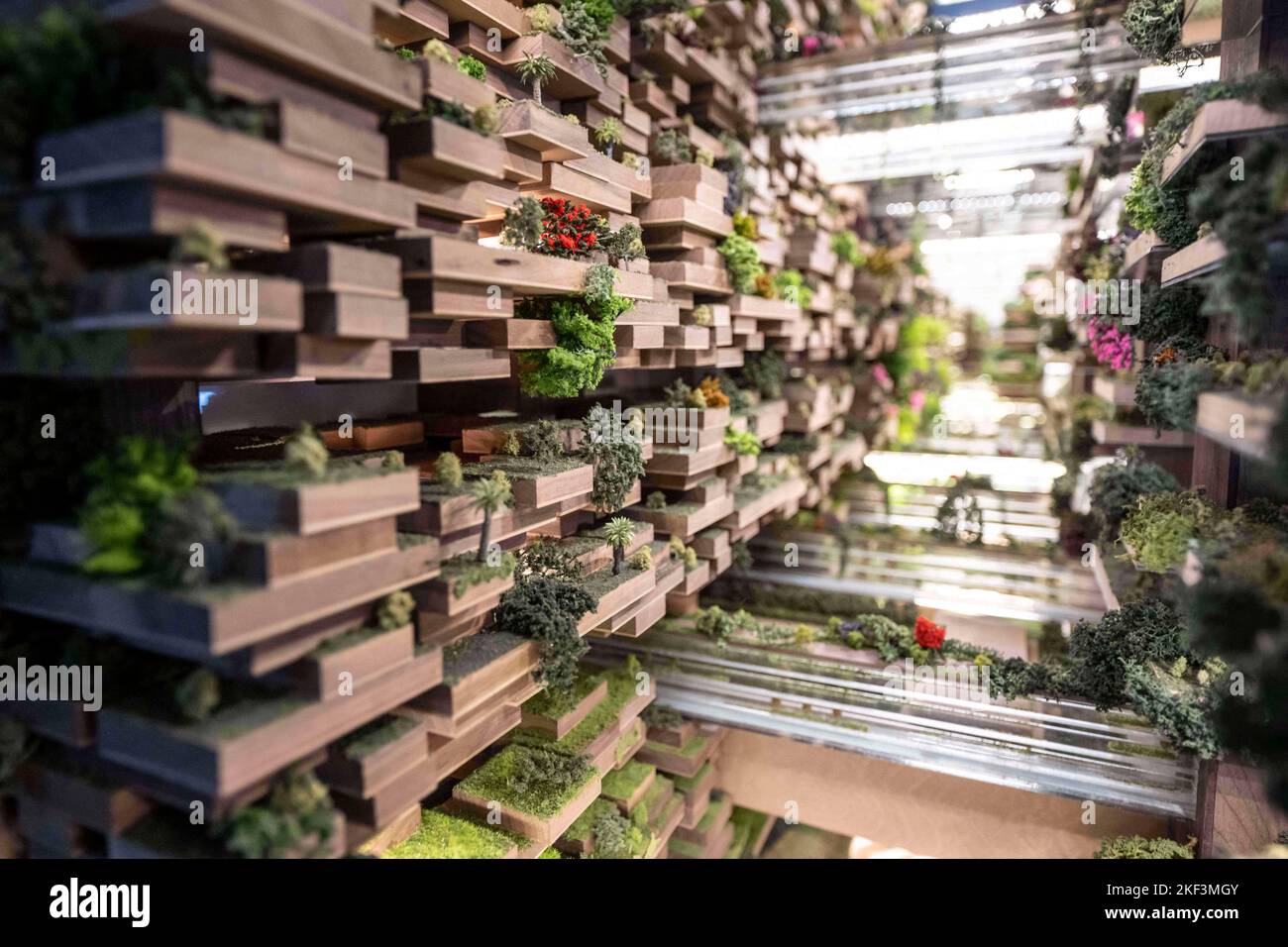

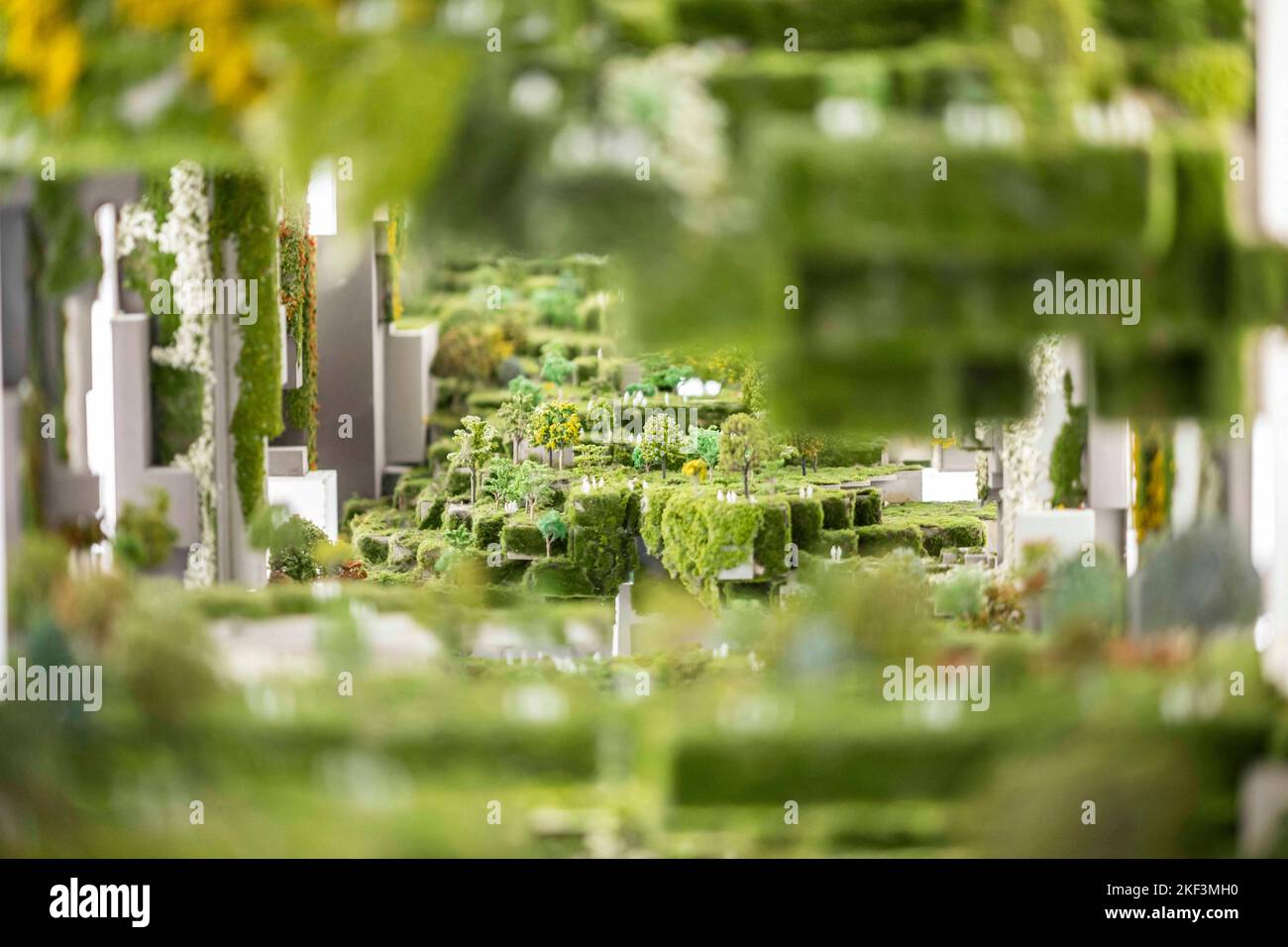

Andreas . P .Design & Modellierungs Corp.LTD ( Continuation ) / 2 Slider / Growth Graphically Articulated Design / A.P.P Source / 21.04.2024 / Release Date 05.07.2024 02:51

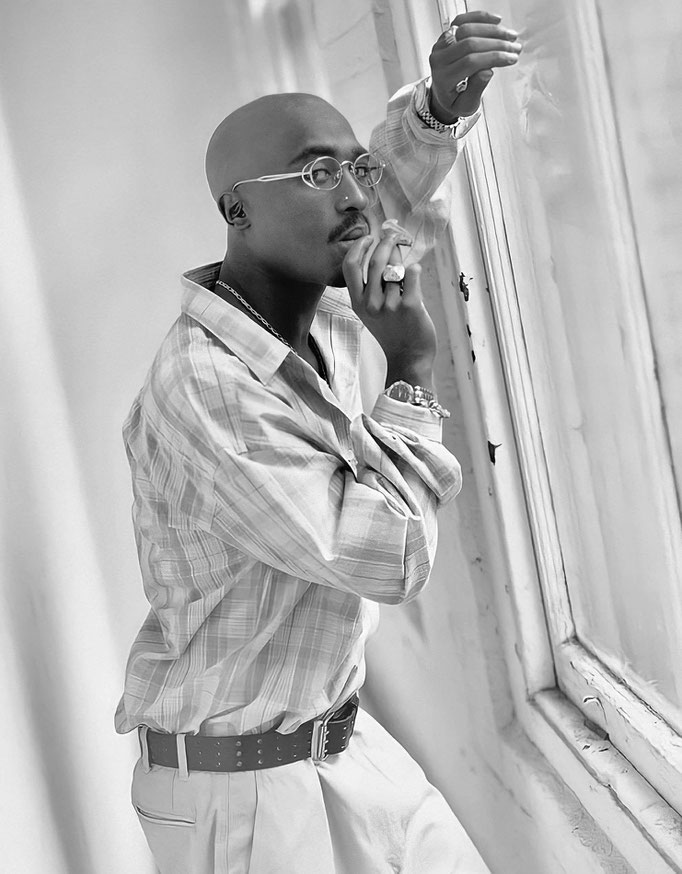

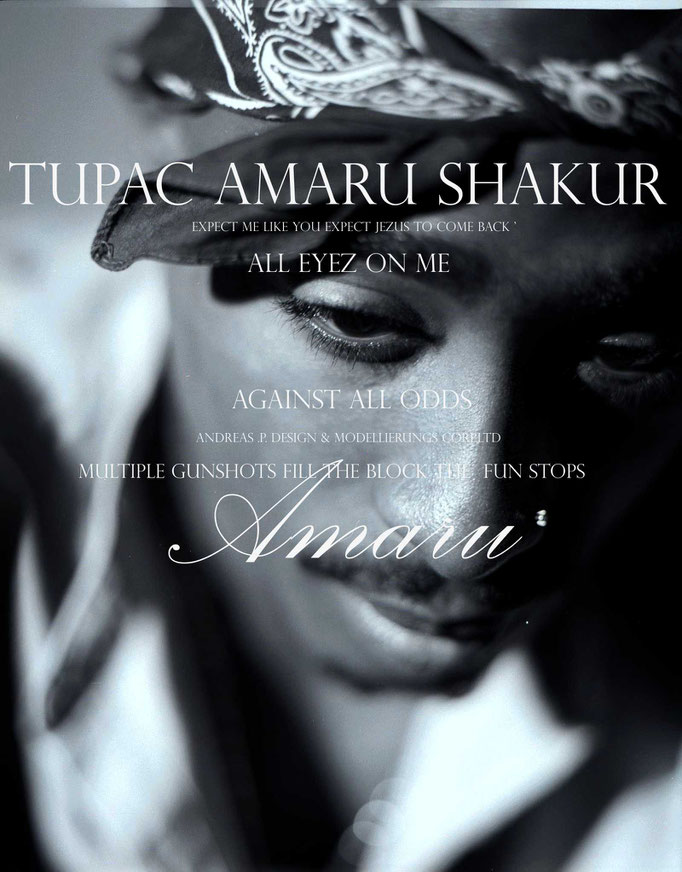

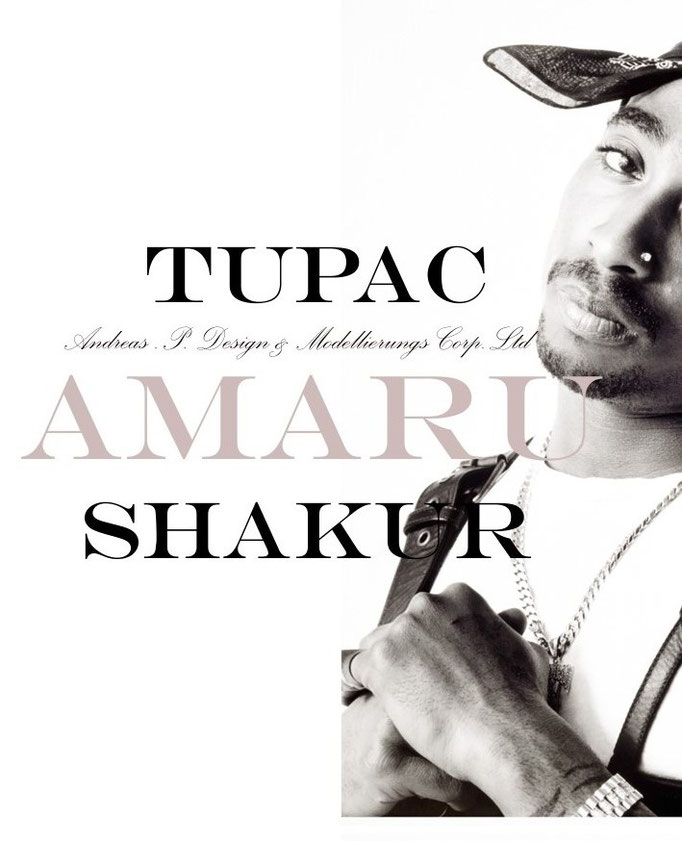

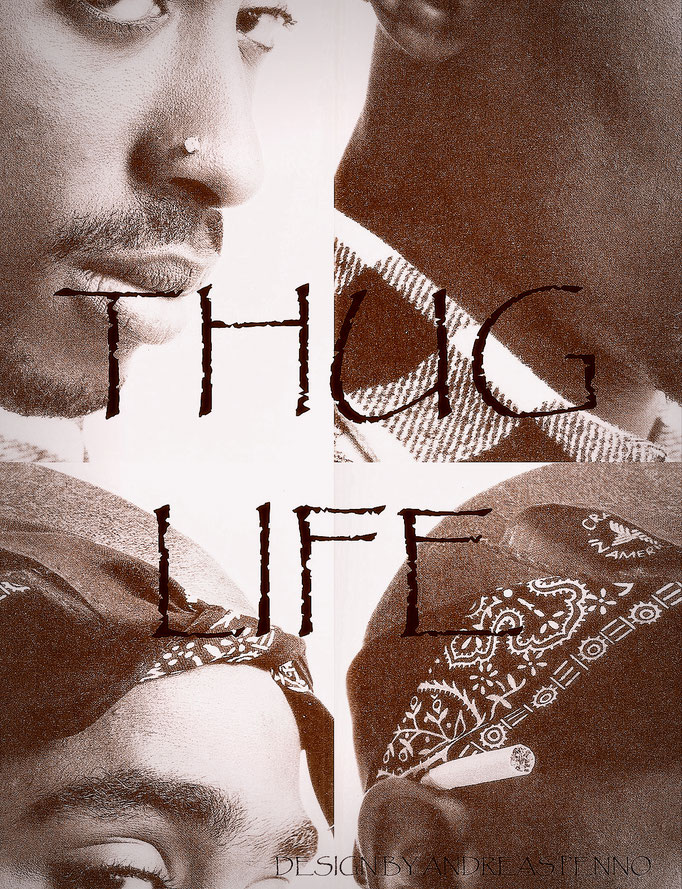

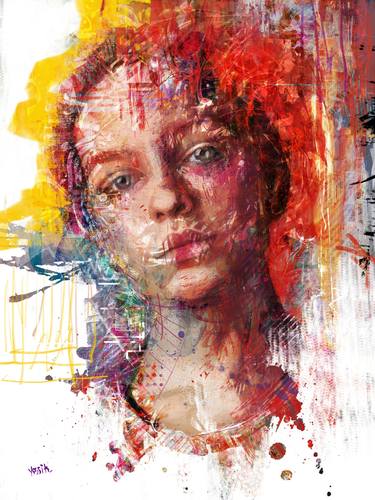

So this Slider is the Continuation of the Graphically Sector Andreas . P. Design & Modellierungs Corp.LTD.This Continuation is all about Pristine Beautifully Graphically Design. So it's an Update ( Slider ). Also Designed from North American Photographers just their ( Original )to my Graphically Components & Structure and Establishment Ground Fundamentally .So also new on Andreas . P. Design & Modellierungs Corp.LTD is Collage Arts just the Contemporary Arts from my Blogspot.Also so this Slider is new Arts,new Creation & Design.So it's an Update ( Slider ).So this Sector World / Transcontinental Art / Works / Creation / Culture is all about Arts.All about Design & Graphically Manufacturing.Creativity,Representation,Establishment.Foundation.Development.Promulgation of Arts & Art.Creational Opportunities & Possibilities.Just on this Sector i represent own created Arts & Establishment of Transcontinnetal Arts Worldwide.Just mostly of this unique Design from my own Design is Tupac Amaru Shakur alias Makaveli.When he lived,he was Great also for the East Coast & New York, USA & World.Just New York, The World Metropolitan Great Scale Hugh City.Also New York is to find on Google linked from this Sector as far as the History & the 21st Century from A.P.P The Source. So Makaveli is oftenly on the Portrayal of the Designer Lounge & Structure and Amalgam Showmanship & Ensemble & Slider. So A.P.P Source represents Ideals of Strong Particular Creative Opportunities & Possibilities.So Check this Sector & my Own Opportunistic Graphically Establishment.So also the whole World Arts Sector represents Franchise Merchandising Marketing on Google Worldwide.So different is Related.

Yours Sincerely,

Andreas Penno

( A.P.P ) Source

Graphically Slider Show Below Update 15.05.2025 AD n.Chr

Michael Miller Photography / ( A. P. P ) Andreas . P . Design & Modellierungs Corp.LTD / Collection Photographers from North America / Transcontinental / EU

Collection of Photographers from Tupac Amaru Shakur / So always standing under Steadily Update & Upgrade from different Resources just standing under Latest Graphically News from ( World Wide Web ) ( Update 09.05.2025 ( n.Chr)

Reisig & Taylor Photography / California/ Los Angeles / Charismatically Photographer & ( Great Portfolio ) World Arts / Street Type / Update 18.04.2025 AD

Dana Lixenberg Photography ( New York Photographer ) USA / Origin Netherlands / Released some Books ( Publications ) In this Time Of Era

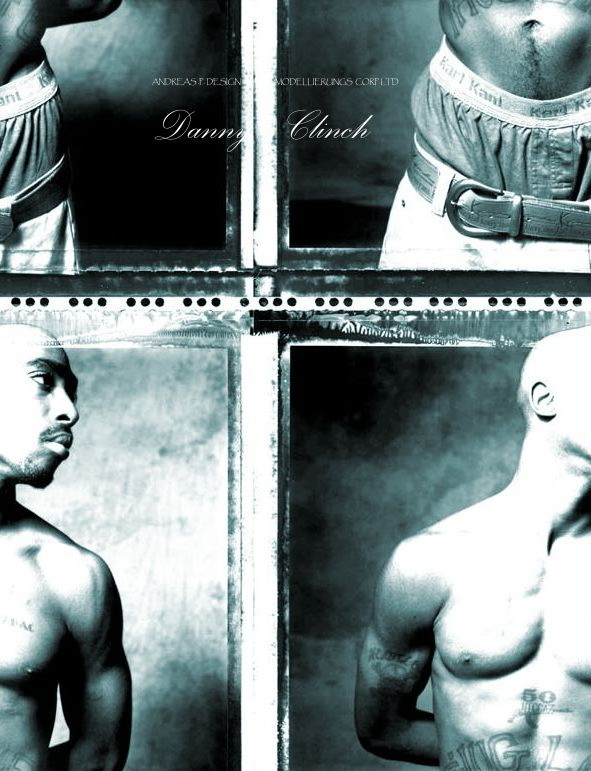

Danny Clinch / NYC / New York Photographer / @ Tupac Amaru Shakur alias ( Makaveli ) Artist in Front of the Camera Lens Spectrum / Streets / Street Print & Knowledge

Michael O'Neill / North America Photographer / U.S / Makaveli / Collage Arts / Collection / Andreas . P . Design & Modellierungs Corp.LTD /( Update ) 03.03.2025

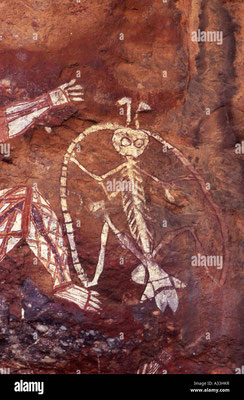

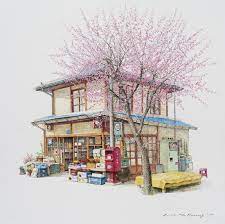

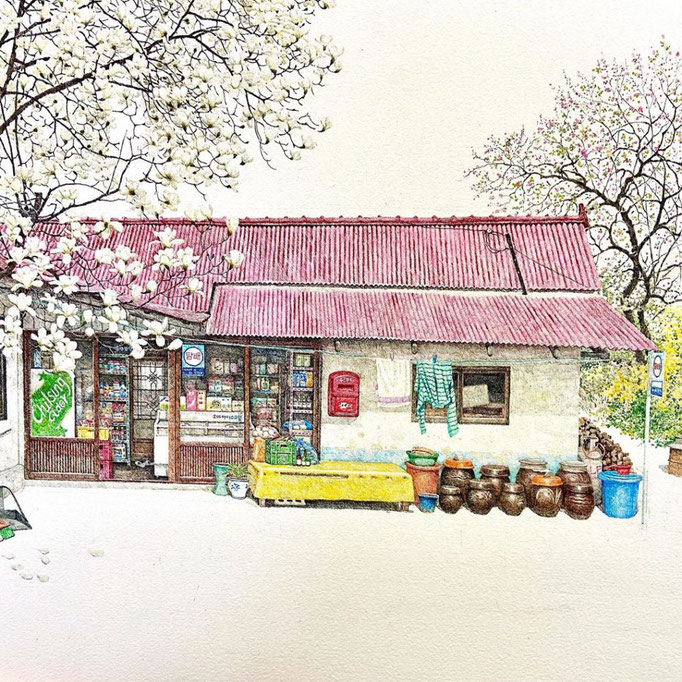

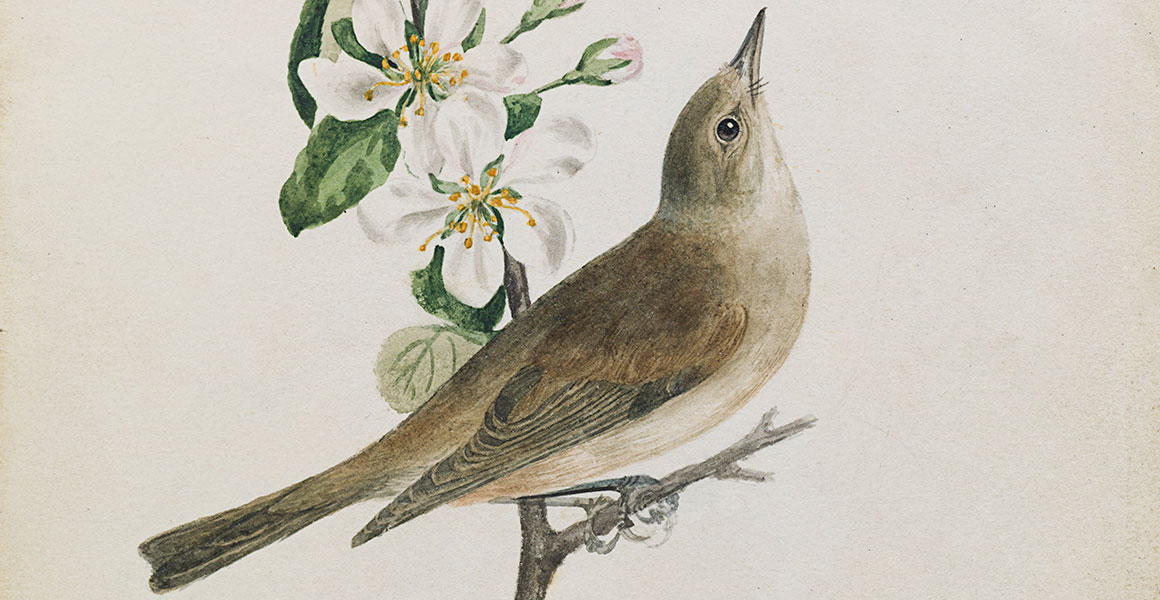

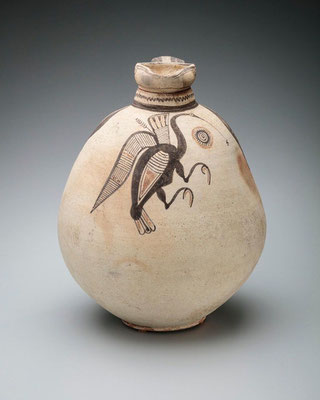

Protokollierung / Historically Paintings & Drawings from Japanese Art Illustrated / Include a Volcano Image / Protokoll / 15.11.2022 AD

Japanese Art

Japanese art covers a wide range of art styles and media, including ancient pottery, sculpture, ink painting and calligraphy on silk and paper, ukiyo-e paintings and woodblock prints, ceramics, origami, and more recently manga and anime. It has a long history, ranging from the beginnings of human habitation in Japan, sometime in the 10th millennium BC, to the present-day country.

Japan has been subject to sudden invasions of new ideas followed by long periods of minimal contact with the outside world. Over time the Japanese developed the ability to absorb, imitate, and finally assimilate those elements of foreign culture that complemented their aesthetic preferences. The earliest complex art in Japan was produced in the 7th and 8th centuries in connection with Buddhism. In the 9th century, as the Japanese began to turn away from China and develop indigenous forms of expression, the secular arts became increasingly important; until the late 15th century, both religious and secular arts flourished. After the Ōnin War (1467–1477), Japan entered a period of political, social, and economic disruption that lasted for over a century. In the state that emerged under the leadership of the Tokugawa shogunate, organized religion played a much less important role in people's lives, and the arts that survived were primarily secular. The Meiji Period (1868-1912) saw an abrupt influx of Western styles, which have continued to be important.

Painting is the preferred artistic expression in Japan, practiced by amateurs and professionals alike. Until modern times, the Japanese wrote with a brush rather than a pen, and their familiarity with brush techniques has made them particularly sensitive to the values and aesthetics of painting. With the rise of popular culture in the Edo period, a style of woodblock prints became a major form and its techniques were fine-tuned to produce colorful prints. The Japanese, in this period, found sculpture a much less sympathetic medium for artistic expression; most large Japanese sculpture is associated with religion, and the medium's use declined with the lessening importance of traditional Buddhism.

Japanese pottery is among the finest in the world[citation needed] and includes the earliest known Japanese artifacts; Japanese export porcelain has been a major industry at various points. Japanese lacquerware is also one of the world's leading arts and crafts, and works gorgeously decorated with maki-e were exported to Europe and China, remaining important exports until the 19th century.[1][2] In architecture, Japanese preferences for natural materials and an interaction of interior and exterior space are clearly expressed.

History of Japanese art

Jōmon art

The first settlers of Japan were the Jōmon people (c. 10,500 – c. 300 BCE),[3] named for the cord markings that decorated the surfaces of their clay vessels, were nomadic hunter-gatherers who later practiced organized farming and built cities with populations of hundreds if not thousands. They built simple houses of wood and thatch set into shallow earthen pits to provide warmth from the soil. They crafted lavishly decorated pottery storage vessels, clay figurines called dogū, and crystal jewels.

Early Jōmon period

During the Early Jōmon period (5000-2500 BCE),[3] villages started to be discovered and ordinary everyday objects were found such as ceramic pots purposed for boiling water. The pots that were found during this time had flat bottoms and had elaborate designs made out of materials such as bamboo. In addition, another important find was the early Jōmon figurines which might have been used as fertility objects due to the breasts and swelling hips that they exhibited.[3]

The Middle Jōmon period (2500-1500 BCE),[3] contrasted from the Early Jōmon Period in many ways. These people became less nomadic and began to settle in villages. They created useful tools that were able to process the food that they gathered and hunted which made living easier for them. Through the numerous aesthetically pleasing ceramics that were found during this time period, it is evident that these people had a stable economy and more leisure time to establish beautiful pieces. In addition, the people of the Middle Jōmon period differed from their preceding ancestors because they developed vessels according to their function, for example, they produced pots in order to store items.[3] The decorations on these vessels started to become more realistic looking as opposed to the early Jōmon ceramics. Overall, the production of works not only increased during this period, but these individuals made them more decorative and naturalistic.[3]

Late and Final Jōmon period

During the Late and Final Jōmon period (1500-300 BCE),[3] the weather started to get colder, therefore forcing them to move away from the mountains. The main food source during this time was fish, which made them improve their fishing supplies and tools. This advancement was a very important achievement during this time. In addition, the numbers of vessels largely increased which could possibly conclude that each house had their own figurine displayed in them. Although various vessels were found during the Late and Final Jōmon Period, these pieces were found damaged which might indicate that they used them for rituals. In addition, figurines were also found and were characterized by their fleshy bodies and goggle like eyes.[3]

Dogū figurines

Dogū

Dogū ("earthen figure") are small humanoid and animal figurines made during the later part of the Jōmon period.[4] They were made across all of Japan, except Okinawa.[4] Some scholars theorize the dogū acted as effigies of people, that manifested some kind of sympathetic magic.[5] Dogū are made of clay and are small, typically 10 to 30 cm high.[6] Most of the figurines appear to be modeled as female, and have big eyes, small waists, and wide hips.[4] They are considered by many to be representative of goddesses. Many have large abdomens associated with pregnancy, suggesting that the Jomon considered them mother goddesses.

Affiliated

The earliest Japanese sculptures of the Buddha are dated to the 6th and 7th century.[10] They ultimately derive from the 1st- to 3rd-century AD Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara, characterized by flowing dress patterns and realistic rendering,[11] on which Chinese artistic traits were superimposed. After the Chinese Northern Wei buddhist art had infiltrated a Korean peninsula, Buddhist icons were brought to Japan by Various immigrant groups.[12] Particularly, the semi-seated Maitreya form was adapted into a highly developed Ancient Greek art style which was transmitted to Japan as evidenced by the Kōryū-ji Miroku Bosatsu and the Chūgū-ji Siddhartha statues.[13] Many historians portray Korea as a mere transmitter of Buddhism.[14] The Three Kingdoms, and particularly Baekje, were instrumental as active agents in the introduction and formation of a Buddhist tradition in Japan in 538 or 552.[15] They illustrate the terminal point of the Silk Road transmission of art during the first few centuries of our era. Other examples can be found in the development of the iconography of the Japanese Fūjin Wind God,[16] the Niō guardians,[17] and the near-Classical floral patterns in temple decorations.[18]

The earliest Buddhist structures still extant in Japan, and the oldest wooden buildings in the Far East are found at the Hōryū-ji to the southwest of Nara. First built in the early 7th century as the private temple of Crown Prince Shōtoku, it consists of 41 independent buildings. The most important ones, the main worship hall, or Kondō (Golden Hall), and Gojū-no-tō (Five-story Pagoda), stand in the center of an open area surrounded by a roofed cloister. The Kondō, in the style of Chinese worship halls, is a two-story structure of post-and-beam construction, capped by an irimoya, or hipped-gabled roof of ceramic tiles.

Inside the Kondō, on a large rectangular platform, are some of the most important sculptures of the period. The central image is a Shaka Trinity (623), the historical Buddha flanked by two bodhisattvas, sculpture cast in bronze by the sculptor Tori Busshi (flourished early 7th century) in homage to the recently deceased Prince Shōtoku. At the four corners of the platform are the Guardian Kings of the Four Directions, carved in wood around 650. Also housed at Hōryū-ji is the Tamamushi Shrine, a wooden replica of a Kondō, which is set on a high wooden base that is decorated with figural paintings executed in a medium of mineral pigments mixed with lacquer.

Temple building in the 8th century was focused around the Tōdai-ji in Nara. Constructed as the headquarters for a network of temples in each of the provinces, the Tōdaiji is the most ambitious religious complex erected in the early centuries of Buddhist worship in Japan. Appropriately, the 16.2-m (53-ft) Buddha (completed 752) enshrined in the main Buddha hall, or Daibutsuden, is a Rushana Buddha, the figure that represents the essence of Buddhahood, just as the Tōdaiji represented the center for Imperially sponsored Buddhism and its dissemination throughout Japan. Only a few fragments of the original statue survive, and the present hall and central Buddha are reconstructions from the Edo period.

Clustered around the Daibutsuden on a gently sloping hillside are a number of secondary halls: the Hokke-dō (Lotus Sutra Hall), with its principal image, the Fukukenjaku Kannon (不空羂索観音立像, the most popular bodhisattva), crafted of dry lacquer (cloth dipped in lacquer and shaped over a wooden armature); the Kaidanin (戒壇院, Ordination Hall) with its magnificent clay statues of the Four Guardian Kings; and the storehouse, called the Shōsōin. This last structure is of great importance as an art-historical cache, because in it are stored the utensils that were used in the temple's dedication ceremony in 752, the eye-opening ritual for the Rushana image, as well as government documents and many secular objects owned by the Imperial family.

Choukin (or chōkin), the art of metal engraving or sculpting, is thought to have started in the Nara period.

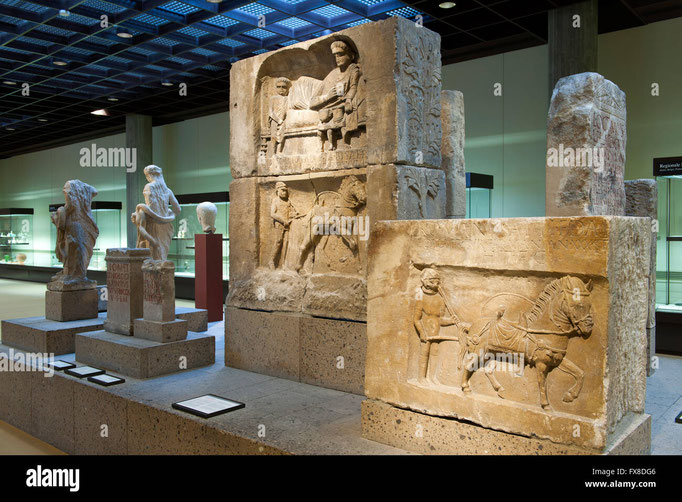

World / News / ( Egypt ) / Middle East / Red Sea / Ancient Arts & Artefacts from Egyptian Abu Simbel Temple & Complex & Different Related / Protokoll 26.11.2022

Abu Simbel, site of two temples built by the Egyptian king Ramses II (reigned 1279–13 BCE), now located in Aswān muḥāfaẓah (governorate), southern Egypt. In ancient times the area was at the southern frontier of pharaonic Egypt, facing Nubia. The four colossal statues of Ramses in front of the main temple are spectacular examples of ancient Egyptian art. By means of a complex engineering feat in the 1960s, the temples were salvaged from the rising waters of the Nile River caused by erection of the Aswan High Dam.

Carved out of a sandstone cliff on the west bank of the Nile, south of Korosko (modern Kuruskū), the temples were unknown to the outside world until their rediscovery in 1813 by the Swiss researcher Johann Ludwig Burckhardt. They were first explored in 1817 by the early Egyptologist Giovanni Battista Belzoni.

Temple ruins of columns and statures at Karnak, Egypt (Egyptian architecture; Egyptian archaelogy; Egyptian history)

You know basic history facts inside and out. But what about the details in between? Put your history smarts to the test to see if you qualify for the title of History Buff.The 66-foot (20-metre) seated figures of Ramses are set against the recessed face of the cliff, two on either side of the entrance to the main temple. Carved around their feet are small figures representing Ramses’ children, his queen, Nefertari, and his mother, Muttuy (Mut-tuy, or Queen Ti). Graffiti inscribed on the southern pair by Greek mercenaries serving Egypt in the 6th century BCE have provided important evidence of the early history of the Greek alphabet. The temple itself, dedicated to the sun gods Amon-Re and Re-Horakhte, consists of three consecutive halls extending 185 feet (56 metres) into the cliff, decorated with more Osiride statues of the king and with painted scenes of his purported victory at the Battle of Kadesh. On two days of the year (about February 22 and October 22), the first rays of the morning sun penetrate the whole length of the temple and illuminate the shrine in its innermost sanctuary.

Just to the north of the main temple is a smaller one, dedicated to Nefertari for the worship of the goddess Hathor and adorned with 35-foot (10.5-metre) statues of the king and queen.

In the mid-20th century, when the reservoir that was created by the construction of the nearby Aswan High Dam threatened to submerge Abu Simbel, UNESCO and the Egyptian government sponsored a project to save the site. An informational and fund-raising campaign was initiated by UNESCO in 1959. Between 1963 and 1968 a workforce and an international team of engineers and scientists, supported by funds from more than 50 countries, dug away the top of the cliff and completely disassembled both temples, reconstructing them on high ground more than 200 feet (60 metres) above their previous site. In all, some 16,000 blocks were moved. In 1979 Abu Simbel, Philae, and other nearby monuments were collectively designated a UNESCO World Heritage site.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica ( Resource )

This article was most recently revised and updated by Adam Zeidan.

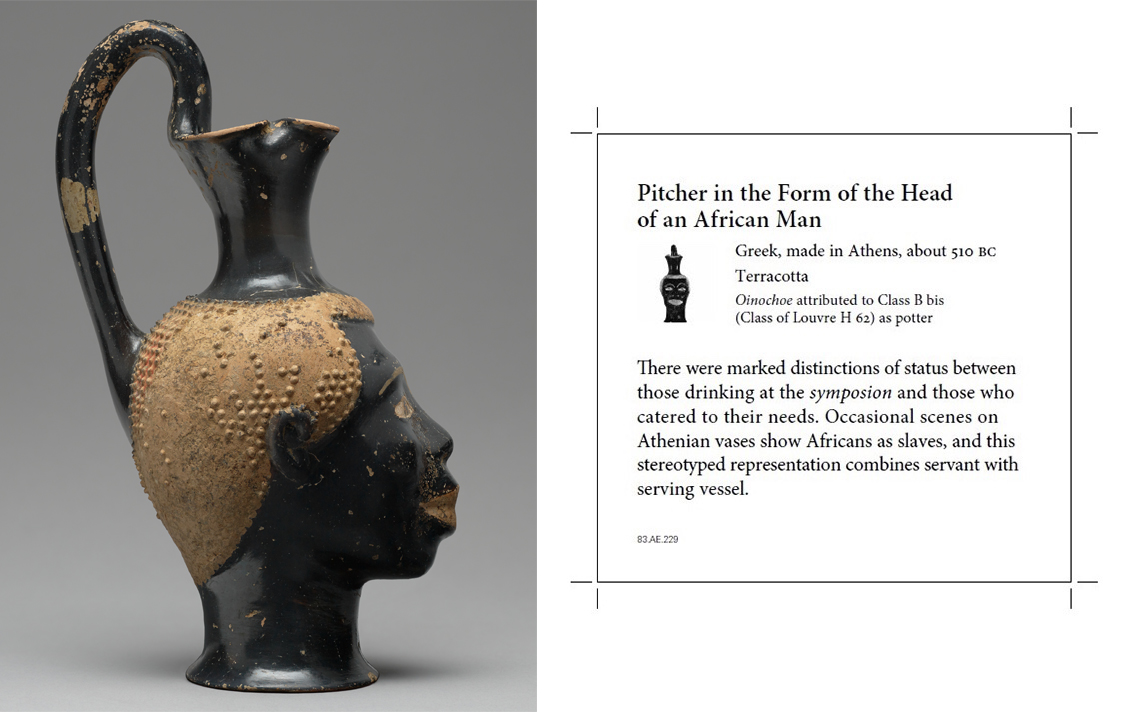

Ancient Egyptian art refers to art produced in ancient Egypt between the 6th millennium BC and the 4th century AD, spanning from Prehistoric Egypt until the Christianization of Roman Egypt. It includes paintings, sculptures, drawings on papyrus, faience, jewelry, ivories, architecture, and other art media. It is also very conservative: the art style changed very little over time. Much of the surviving art comes from tombs and monuments, giving more insight into the ancient Egyptian afterlife beliefs.

The ancient Egyptian language had no word for "art". Artworks served an essentially functional purpose that was bound with religion and ideology. To render a subject in art was to give it permanence. Therefore, ancient Egyptian art portrayed an idealized, unrealistic view of the world. There was no significant tradition of individual artistic expression since art served a wider and cosmic purpose of maintaining order (Ma'at).

Art of Pre-Dynastic Egypt (6000–3000 BC)

Pre-Dynastic Egypt, corresponding to the Neolithic period of the prehistory of Egypt, spanned from c. 6000 BC to the beginning of the Early Dynastic Period, around 3100 BC.

Continued expansion of the desert forced the early ancestors of the Egyptians to settle around the Nile and adopt a more sedentary lifestyle during the Neolithic. The period from 9000 to 6000 BC has left very little archaeological evidence, but around 6000 BC, Neolithic settlements began to appear all over Egypt.[1] Studies based on morphological,[2] genetic,[3] and archaeological data[4] have attributed these settlements to migrants from the Fertile Crescent returning during the Neolithic Revolution, bringing agriculture to the region.[5]

Merimde culture (5000–4200 BC)

From about 5000 to 4200 BC, the Merimde culture, known only from a large settlement site at the edge of the Western Nile Delta, flourished in Lower Egypt. The culture has strong connections to the Faiyum A culture as well as the Levant. People lived in small huts, produced simple undecorated pottery, and had stone tools. Cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs were raised, and wheat, sorghum and barley were planted. The Merimde people buried their dead within the settlement and produced clay figurines.[6] The first Egyptian life-size head made of clay comes from Merimde.[7]

Badarian culture (4400–4000 BC)

The Badarian culture, from about 4400 to 4000 BC,[8] is named for the Badari site near Der Tasa. It followed the Tasian culture (c. 4500 BC) but was so similar that many consider them one continuous period. The Badarian culture continued to produce blacktop-ware pottery (albeit much improved in quality) and was assigned sequence dating (SD) numbers 21–29.[9] The primary difference that prevents scholars from merging the two periods is that Badarian sites use copper in addition to stone and are thus chalcolithic settlements, while the Neolithic Tasian sites are still considered Stone Age.

Art of Dynastic Egypt

Early Dynastic Period (3100–2685 BC)

The Early Dynastic Period of Egypt immediately follows the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, c. 3100 BC. It is generally taken to include the First and Second Dynasties, lasting from the end of the Naqada III archaeological period until about 2686 BC, or the beginning of the Old Kingdom.[8]

Cosmetic palettes reached a new level of sophistication during this period, in which the Egyptian writing system also experienced further development. Initially, Egyptian writing was composed primarily of a few symbols denoting amounts of various substances. In the cosmetic palettes, symbols were used together with pictorial descriptions. By the end of the Third Dynasty, this had been expanded to include more than 200 symbols, both phonograms and ideograms.[20]

Second Intermediate Period (c. 1650–1550 BC)

The Hyksos, a dynasty of ruler originating from the Levant, do not appear to have produced any court art,[32] instead appropriating monuments from earlier dynasties by writing their names on them. Many of these are inscribed with the name of King Khyan.[33] A large palace at Avaris has been uncovered, built in the Levantine rather than the Egyptian style, most likely by Khyan.[34] King Apepi is known to have patronized Egyptian scribal culture, commissioning the copying of the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus.[35] The stories preserved in the Westcar Papyrus may also date from his reign.[36]

The so-called "Hyksos sphinxes" or "Tanite sphinxes" are a group of royal sphinxes depicting the earlier Pharaoh Amenemhat III (Twelfth Dynasty) with some unusual traits compared to conventional statuary, for example prominent cheekbones and the thick mane of a lion, instead of the traditional nemes headcloth. The name "Hyksos sphinxes" was given due to the fact that these were later reinscribed by several of the Hyksos kings, and were initially thought to represent the Hyksos kings themselves. Nineteenth-century scholars attempted to use the statues' features to assign a racial origin to the Hyksos.[37] These sphinxes were seized by the Hyksos from cities of the Middle Kingdom and then transported to their capital Avaris where they were reinscribed with the names of their new owners and adorned their palace.[31] Seven of those sphinxes are known, all from Tanis, and now mostly located in the Cairo Museum.[31][38] Other statues of Amenehat III were found in Tanis and are associated with the Hyksos in the same manner.

Metals

While not a leading center of metallurgy, ancient Egypt nevertheless developed technologies for extracting and processing the metals found within its borders and in neighbouring lands. Copper was the first metal to be exploited in Egypt. Small beads have been found in Badarian graves; larger items were produced in the later Predynastic Period, by a combination of mould-casting, annealing and cold-hammering. The production of copper artifacts peaked in the Old Kingdom when huge numbers of copper chisels were manufactured to cut the stone blocks of pyramids. The copper statues of Pepi I and Merenre from Hierakonpolis are rare survivors of large-scale metalworking. The golden treasure of Tutankhamun has come to symbolize the wealth of ancient Egypt, and illustrates the importance of gold in pharaonic culture. The burial chamber in a royal tomb was called "the house of gold". According to the Egyptian religion, the flesh of the gods was made of gold. A shining metal that never tarnished, it was the ideal material for cult images of deities, for royal funerary equipment, and to add brilliance to the tops of obelisks. It was used extensively for jewelry, and was distributed to officials as a reward for loyal services ("the gold of honour").Silver had to be imported from the Levant, and its rarity initially gave it greater value than gold (which, like electrum, was readily available within the borders of Egypt and Nubia). Early examples of silverwork include the bracelets of the Hetepheres. By the Middle Kingdom, silver seems to have become less valuable than gold, perhaps because of increased trade with the Middle East. The treasure from El-Tod consisted of a hoard of silver objects, probably made in the Aegean, while silver jewelry made for female members of the 12th Dynasty royal family was found at Dahshur and Lahun. In the Egyptian religion, the bones of the gods were said to be made of silver.Iron was the last metal to be exploited on a large scale by the Egyptians. Meteoritic iron was used for the manufacture of beads from the Badarian period. However, the advanced technology required to smelt iron was not introduced into Egypt until the Late Period. Before that, iron objects were imported and were consequently highly valued for their rarity. The Amarna letters refer to diplomatic gifts of iron being sent by Near Eastern rulers, especially the Hittites, to Amenhotep III and Akhenaten. Iron tools and weapons only became common in Egypt in the Roman Period.

Wood

Because of its relatively poor survival in archaeological contexts, wood is not particularly well represented among artifacts from Ancient Egypt. Nevertheless, woodworking was evidently carried out to a high standard from an early period. Native trees included date palm and dom palm, the trunks of which could be used as joists in buildings, or split to produce planks. Tamarisk, acacia and sycamore fig were employed in furniture manufacture, while ash was used when greater flexibility was required (for example in the manufacture of bowls). However, all these native timbers were of relatively poor quality; finer varieties had to be imported, especially from the Levant.

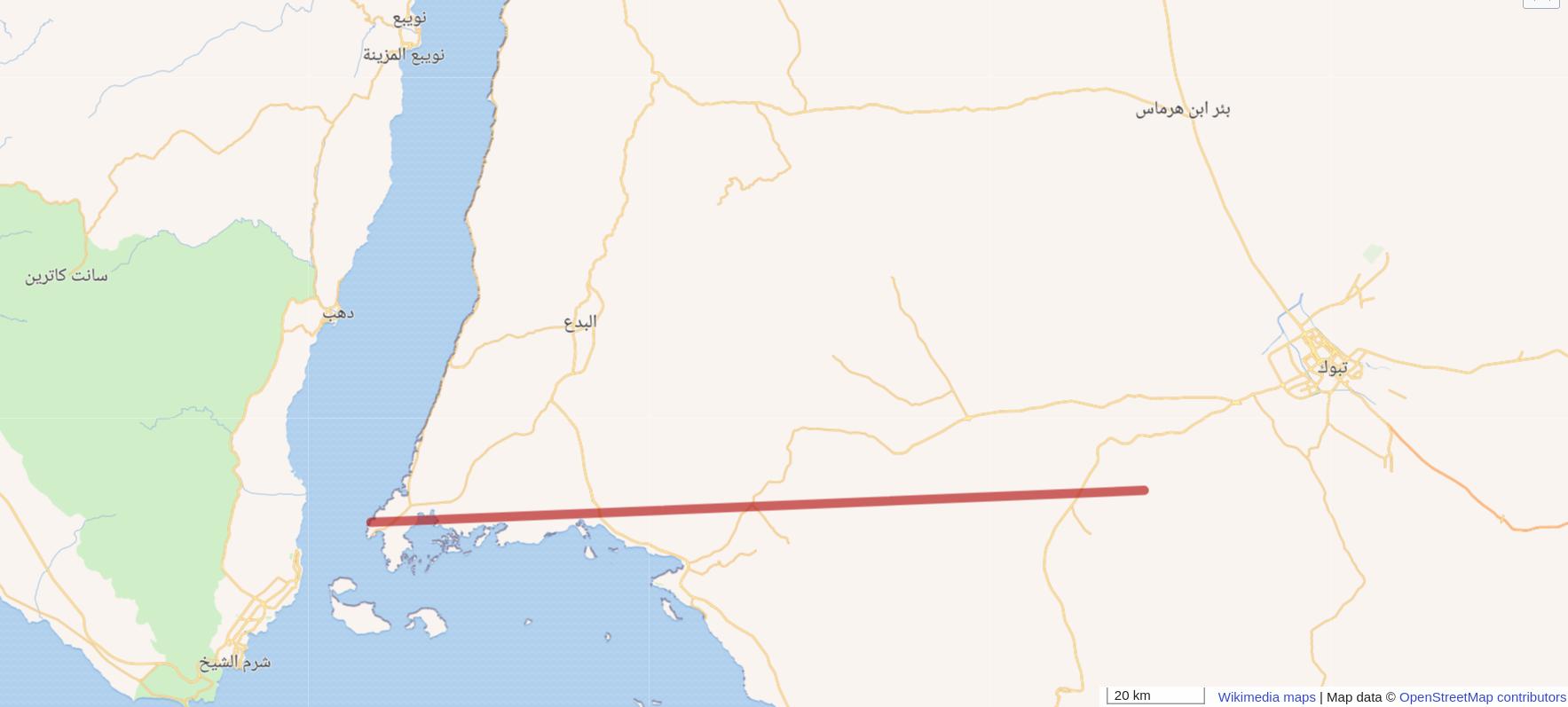

Abu Simbel / Temple / Egypt / Nile / Middle East / Also Connectivity to Kingdom of Saudi Arabia ( NEOM ) / Protokoll / 26.11.2022 AD

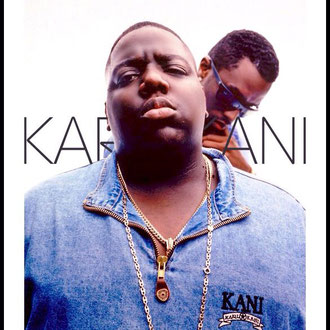

The Notorious B.I.G / Art / One of the Most Notorious Figures & Personalities in the History of New York / ( Wikipedia Source ) / 01.12.2022 / Protokollierung

Christopher George Latore Wallace (May 21, 1972 – March 9, 1997), better known by his stage names the Notorious B.I.G., Biggie Smalls, or simply Biggie,[2] was an American rapper. Rooted in East Coast hip hop and particularly gangsta rap, he is widely considered one of the greatest rappers of all time. Wallace became known for his distinctive laid-back lyrical delivery, offsetting the lyrics' often grim content. His music was often semi-autobiographical, telling of hardship and criminality, but also of debauchery and celebration.[3]Born and raised in Brooklyn, New York City, Wallace signed to Sean "Puffy" Combs' label Bad Boy Records as it launched in 1993, and gained exposure through features on several other artists' singles that year. His debut album Ready to Die (1994) was met with widespread critical acclaim, and included his signature songs "Juicy" and "Big Poppa". The album made him the central figure in East Coast hip hop, and restored New York's visibility at a time when the West Coast hip hop scene was dominating hip hop music.[4] Wallace was awarded the 1995 Billboard Music Awards' Rapper of the Year.[5] The following year, he led his protégé group Junior M.A.F.I.A., a team of himself and longtime friends, including Lil' Kim, to chart success.

During 1996, while recording his second album, Wallace became ensnarled in the escalating East Coast–West Coast hip hop feud. Following Tupac Shakur's death in a drive-by shooting in Las Vegas in September 1996, speculations of involvement in Shakur's murder by criminal elements orbiting the Bad Boy circle circulated as a result of Wallace's public feud with Shakur. On March 9, 1997, six months after Shakur's death, Wallace was murdered by an unidentified assailant in a drive-by shooting while visiting Los Angeles. Wallace's second album Life After Death, a double album, was released two weeks later. It reached number one on the Billboard 200, and eventually achieved a diamond certification in the United States.[6]With two more posthumous albums released, Wallace has certified sales of over 28 million copies in the United States,[7] including 21 million albums.[8] Rolling Stone has called him the "greatest rapper that ever lived",[9] and Billboard named him the greatest rapper of all time.[10] The Source magazine named him the greatest rapper of all time in its 150th issue. In 2006, MTV ranked him at No. 3 on their list of The Greatest MCs of All Time, calling him possibly "the most skillful ever on the mic".[11] In 2020, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Life and career

1972–1991: Early life

Christopher George Latore Wallace was born at St. Mary's Hospital in the New York City borough of Brooklyn on May 21, 1972, the only child of Jamaican immigrant parents. His mother, Voletta Wallace, was a preschool teacher, while his father, Selwyn George Latore, was a welder and politician.[12][13] His father left the family when Wallace was two years old, and his mother worked two jobs while raising him. Wallace grew up at 226 St. James Place in Brooklyn's Clinton Hill,[14] near the border with Bedford-Stuyvesant.[12][15] Raised Catholic, Wallace excelled at Queen of All Saints Middle School, winning several awards as an English student. He attended St Peter Claver Church in the borough.[16] He was nicknamed "Big" because he was overweight by the age of 10.[17] Wallace claimed to have begun dealing drugs at about age 12. His mother, often at work, first learned of this during his adulthood.[18]

He began rapping as a teenager, entertaining people on the streets, and performed with local groups, the Old Gold Brothers as well as the Techniques.[19] His earliest stage name was MC CWest.[20] At his request, Wallace transferred from Bishop Loughlin Memorial High School in Fort Greene to George Westinghouse Career and Technical Education High School in Downtown Brooklyn, which future rappers Jay-Z and Busta Rhymes were also attending. According to his mother, Wallace was still a good student but developed a "smart-ass" attitude at the new school.[13] At age 17 in 1989, Wallace dropped out of high school and became more involved in crime. That same year in 1989, he was arrested on weapons charges in Brooklyn and sentenced to five years' probation. In 1990, he was arrested on a violation of his probation.[21] A year later, Wallace was arrested in North Carolina for dealing crack cocaine. He spent nine months in jail before making bail.[18]

1991–1994: Early career and first child

After release from jail, Wallace made a demo tape, Microphone Murderer, while calling himself Biggie Smalls, alluding both to Calvin Lockhart's character in the 1975 film Let's Do It Again and to his own stature and obesity, 6 feet 3 inches (1.91 m) and 300 to 380 lb (140–170 kg).[22] Although Wallace reportedly lacked real ambition for the tape, local DJ Mister Cee, of Big Daddy Kane and Juice Crew association, discovered and promoted it, thus it was heard by The Source rap magazine's editor in 1992.[21]In March, The Source column "Unsigned Hype", dedicated to airing promising rappers, featured Wallace.[23] He then spun the attention into a recording.[23] Upon hearing the demo tape, Sean "Puffy" Combs, still with the A&R department of Uptown Records, arranged to meet Wallace. Promptly signed to Uptown, Wallace appeared on labelmates Heavy D & the Boyz's 1993 song "A Buncha Niggas".[19][24] Mid-year, or a year after Wallace's signing, Uptown fired Combs, who, a week later, launched Bad Boy Records,[25] instantly Wallace's new label.[26]On August 8, 1993, Wallace's longtime girlfriend gave birth to his first child, T'yanna,[26] although the couple had split by then.[27] A high-school dropout, Wallace promised his daughter "everything she wanted", in his reasoning that if he had had the same in childhood, he would have graduated at the top of his class.[28] Although he continued dealing drugs, Combs discovered that and obliged him to quit.[19] Later that year, Wallace gained exposure on a remix of Mary J. Blige's single "Real Love". Having found his moniker Biggie Smalls already claimed, he took a new one, holding for good, The Notorious B.I.G.[29]Around this time, Wallace became friends with fellow rapper Tupac Shakur. Lil' Cease recalled the pair as close, often traveling together whenever they were not working. According to him, Wallace was a frequent guest at Shakur's home and they spent time together when Shakur was in California or Washington, D.C.[30] Yukmouth, an Oakland emcee, claimed that Wallace's style was inspired by Shakur.[31]The "Real Love" remix single was followed by another remix of a Mary J. Blige song, "What's the 411?" Wallace's successes continued, if to a lesser extents, on remixes of Neneh Cherry's song "Buddy X" and of reggae artist Super Cat's song "Dolly My Baby", also featuring Combs, all in 1993. In April, Wallace's solo track "Party and Bullshit" was released on the Who's the Man? soundtrack.[32] In July 1994, he appeared alongside LL Cool J and Busta Rhymes on a remix of his own labelmate Craig Mack's "Flava in Ya Ear", the remix reaching No. 9 on the Billboard Hot 100.[33]

1994: Ready to Die and marriage to Faith Evans

On August 4, 1994, Wallace married R&B singer Faith Evans, whom he had met eight days prior at a Bad Boy photoshoot.[34] Five days later, Wallace had his first pop chart success as a solo artist with double A-side, "Juicy / Unbelievable", which reached No. 27 as the lead single to his debut album.[35]Ready to Die was released on September 13, 1994. It reached No. 13 on the Billboard 200 chart[36] and was eventually certified four times platinum.[37] The album shifted attention back to East Coast hip hop at a time when West Coast hip hop dominated US charts.[38] It gained strong reviews and has received much praise in retrospect.[38][39] In addition to "Juicy", the record produced two hit singles: the platinum-selling "Big Poppa", which reached No. 1 on the U.S. rap chart,[40] and "One More Chance", which sold 1.1 million copies in 1995.[41][42] Busta Rhymes claimed to have seen Wallace giving out free copies of Ready to Die from his home, which Rhymes reasoned as "his way of marketing himself".[43]Wallace also befriended basketball player Shaquille O'Neal. O'Neal said they were introduced during a listening session for "Gimme the Loot"; Wallace mentioned him in the lyrics and thereby attracted O'Neal to his music. O'Neal requested a collaboration with Wallace, which resulted in the song "You Can't Stop the Reign". According to Combs, Wallace would not collaborate with "anybody he didn't really respect" and that Wallace paid O'Neal his respect by "shouting him out".[44] Wallace later met with O'Neal on Sunset Boulevard in 1997.[45] In 2015, Daz Dillinger, a frequent Shakur collaborator, said that he and Wallace were "cool", with Wallace traveling to meet him to smoke cannabis and record two songs.[46]

1995: Collaboration with Michael Jackson, Junior M.A.F.I.A., success and coastal feud

Wallace worked with pop singer Michael Jackson on the song "This Time Around", featured on Jackson's 1995 album HIStory: Past, Present and Future, Book I.[47] Lil' Cease later claimed that while Wallace met Jackson, he was forced to stay behind, with Wallace citing that he did not "trust Michael with kids" following the 1993 child sexual abuse allegations against Jackson.[48] Engineer John Van Nest and producer Dallas Austin recalled the sessions differently, saying that Wallace was eager to meet Jackson and nearly burst into tears upon doing so.[49]In the summer, Wallace met Charli Baltimore and they became involved in a romantic relationship.[50] Several months into their relationship, she left him a voicemail of a rap verse that she had written and he began encouraging her to pursue a career in rap music.[51]Wallace was booked to a show in Sacramento, When they arrived at the venue they were not a lot of people there, and when they started performing they were getting coins tossed at them. When they left they were held at gunpoint in the venue's parking lot set up by E-40's goons. They were mad over an interview he did with a Canadian magazine, when asked to rank a handful of artists on a scale from one to 10, Wallace gave him a zero. One of Wallace's entourage said to get E-40 on the phone, Wallace explained how they had "got him drunk" and had got him "to say anything", E-40 told his men to stand down and safely escorted them to the airport.[52]In August 1995, Wallace's protégé group, Junior M.A.F.I.A. ("Junior Masters At Finding Intelligent Attitudes"), released their debut album Conspiracy. The group consisted of his friends from childhood and included rappers such as Lil' Kim and Lil' Cease, who went on to have solo careers.[53] The record went gold and its singles, "Player's Anthem" and "Get Money", both featuring Wallace, went gold and platinum. Wallace continued to work with R&B artists, collaborating with R&B groups 112 (on "Only You") and Total (on "Can't You See"), with both reaching the top 20 of the Hot 100. By the end of the year, Wallace was the top-selling male solo artist and rapper on the U.S. pop and R&B charts.[19] In July 1995, he appeared on the cover of The Source with the caption "The King of New York Takes Over", a reference to his alias Frank White, based on a character from the 1990 film King of New York.[54][55] At the Source Awards in August 1995, he was named Best New Artist (Solo), Lyricist of the Year, Live Performer of the Year, and his debut Album of the Year.[56] At the Billboard Awards, he was Rap Artist of the Year.[21]In his year of success, Wallace became involved in a rivalry between the East and West Coast hip hop scenes with Shakur, now his former friend. In an interview with Vibe in April 1995, while serving time in Clinton Correctional Facility, Shakur accused Uptown Records' founder Andre Harrell, Sean Combs, and Wallace of having prior knowledge of a robbery that resulted in him being shot five times and losing thousands of dollars worth of jewelry on the night of November 30, 1994. Though Wallace and his entourage were in the same Manhattan-based recording studio at the time of the shooting, they denied the accusation.[57]Wallace said: "It just happened to be a coincidence that he [Shakur] was in the studio. He just, he couldn't really say who really had something to do with it at the time. So he just kinda' leaned the blame on me."[58] In 2012, a man named Dexter Isaac, serving a life sentence for unrelated crimes, claimed that he attacked Shakur that night and that the robbery was orchestrated by entertainment industry executive and former drug trafficker, Jimmy Henchman.[59]Following his release from prison, Shakur signed to Death Row Records on October 15, 1995. This made Bad Boy Records and Death Row business rivals, and thus intensified the quarrel.[60]

1996: More arrests, accusations regarding Shakur's death, car accident and second child

On March 23, 1996, Wallace was arrested outside a Manhattan nightclub for chasing and threatening to kill two fans seeking autographs, smashing the windows of their taxicab, and punching one of them.[21] He pleaded guilty to second-degree harassment and was sentenced to 100 hours of community service. In mid-1996, he was arrested at his home in Teaneck, New Jersey, for drug and weapons possession charges.[21]During the recording for his second album, Wallace was confronted by Shakur for the first time since "the rumors started" at the Soul Train Awards and a gun was pulled.[61]In June 1996, Shakur released "Hit 'Em Up", a diss track in which he claimed to have had sex with Faith Evans, who was estranged from Wallace at the time, and that Wallace had copied his style and image. Wallace referenced the first claim on Jay-Z's "Brooklyn's Finest", in which he raps: "If Faye have twins, she'd probably have two 'Pacs. Get it? 2Pac's?" However, he did not directly respond to the track, stating in a 1997 radio interview that it was "not [his] style" to respond.[58]On September 7, 1996, Shakur was shot multiple times in a drive-by shooting in Las Vegas and died six days later. Rumors of Wallace's involvement with Shakur's murder spread. In a 2002 Los Angeles Times series titled "Who Killed Tupac Shakur?", based on police reports and multiple sources, Chuck Philips reported that the shooting was carried out by a Compton gang, the Southside Crips, to avenge a beating by Shakur hours earlier, and that Wallace had paid for the gun.[62][63]Los Angeles Times editor Mark Duvoisin wrote that "Philips' story has withstood all challenges to its accuracy, ... [and] remains the definitive account of the Shakur slaying."[64] Wallace's family denied the report,[65] producing documents purporting to show that he was in New York and New Jersey at the time. However, The New York Times called the documents inconclusive, stating:

The pages purport to be three computer printouts from Daddy's House, indicating that Wallace was in the studio recording a song called Nasty Boy on the night Shakur was shot. They indicate that Wallace wrote half the session, was in and out/sat around and laid down a ref, shorthand for a reference vocal, the equivalent of a first take. But nothing indicates when the documents were created. And Louis Alfred, the recording engineer listed on the sheets, said in an interview that he remembered recording the song with Wallace in a late-night session, not during the day. He could not recall the date of the session but said it was likely not the night Shakur was shot. We would have heard about it, Mr. Alfred said."[66]Evans remembered her husband calling her on the night of Shakur's death and crying from shock. She said: "I think it's fair to say he was probably afraid, given everything that was going on at that time and all the hype that was put on this so-called beef that he didn't really have in his heart against anyone." Wayne Barrow, Wallace's co-manager at the time, said Wallace was recording the track "Nasty Boy" the night Shakur was shot.[67] Shortly after Shakur's death, he met with Snoop Dogg, who claimed that Wallace declared he never hated Shakur.[68]

Two days after the death of Shakur, Wallace and Lil' Cease were arrested in Brooklyn for smoking marijuana in public and had their car repossessed.[69] The next day, the dealership chose them a Chevrolet Lumina rental SUV as a substitute, despite Lil' Cease's objections. The vehicle had brake problems but Wallace dismissed them.[70] The car collided with a rail in New Jersey, shattering Wallace's left leg, Lil' Cease's jaw and Charli Baltimore with numerous injuries.[71Wallace spent months in a hospital following the accident. He was temporarily confined to a wheelchair,[19] forced to use a cane,[57] and had to complete therapy. Despite his hospitalization, he continued to work on the album. The accident was referred to in the lyrics of "Long Kiss Goodnight": "Ya still tickle me, I used to be as strong as Ripple be / Til Lil' Cease crippled me."[72.On October 29, 1996, Evans gave birth to Wallace's son, Christopher "C.J." Wallace Jr.[26] The following month, Junior M.A.F.I.A. member Lil' Kim released her debut album, Hard Core, under Wallace's direction while the two were having a "love affair".[19] Lil' Kim recalled being Wallace's "biggest fan" and "his pride and joy".[73] In a 2012 interview, Lil' Kim said Wallace had prevented her from making a remix of the Jodeci single "Love U 4 Life" by locking her in a room. According to her, Wallace said that she was not "gonna go do no song with them",[74] likely because of the group's affiliation with Tupac and Death Row Records.

1997: Life After Death

On January 27, 1997, Wallace was ordered to pay US$41,000 in damages following an incident involving a friend of a concert promoter who claimed Wallace and his entourage beat him following a dispute in May 1995.[75] He faced criminal assault charges for the incident, which remains unresolved, but all robbery charges were dropped.[21] Following the events, Wallace spoke of a desire to focus on his "peace of mind" and his family and friends.[76]In February 1997, Wallace traveled to California to promote his album Life After Death and record a music video for its lead single, "Hypnotize". That month Wallace was involved in a domestic dispute with girlfriend Charli Baltimore at the Four Seasons hotel, over pictures of Wallace and other girls. Wallace had told Lil' Cease the night prior to take the bag out of the room of the photos but never did; she ended up throwing Wallace's ring and watch out the window. They found the watch but did not recover the ring.[77]

Death

On March 8, 1997, Wallace attended Soul Train Awards after-party hosted by Vibe and Qwest Records at the Petersen Automotive Museum.[57] Guests included Evans, Aaliyah and members of the Bloods and Crips gangs.[17] The next day at 12:30 a.m. PST, after the fire department closed the party early due to overcrowding, Wallace left with his entourage in two GMC Suburbans to return to his hotel.[78] He traveled in the front passenger seat alongside associates Damion "D-Roc" Butler, Lil' Cease, and driver Gregory "G-Money" Young. Combs traveled in the other vehicle with two bodyguards. The two trucks were trailed by a Chevrolet Blazer carrying Bad Boy director of security Paul Offord.[17][79]By 12:45 a.m., the streets were crowded with people leaving the party. Wallace's truck stopped at a red light 50 yards (46 m) from the Petersen Automotive Museum, and a black Chevy Impala pulled up alongside it. The Impala's driver, an unidentified African-American man dressed in a blue suit and bow tie, rolled down his window, drew a 9 mm blue-steel pistol, and fired at Wallace's car. Four bullets hit Wallace, and his entourage subsequently rushed him to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, where doctors performed an emergency thoracotomy, but he was pronounced dead at 1:15 a.m.[17] He was 24 years old. His autopsy, which was released 15 years after his death, showed that only the final shot was fatal; it entered through his right hip and struck his colon, liver, heart, and left lung before stopping in his left shoulder.[80]Wallace's funeral was held at the Frank E. Campbell Funeral Chapel in Manhattan on March 18. There were around 350 mourners at the funeral, including Lil' Cease, Queen Latifah, Mase, Faith Evans, SWV, Jay-Z, Damon Dash, DJ Premier, Charli Baltimore, Da Brat, Flavor Flav, Mary J. Blige, Lil' Kim, Run-D.M.C., DJ Kool Herc, Treach, Busta Rhymes, Salt-N-Pepa, DJ Spinderella, Foxy Brown, and Sister Souljah. David Dinkins and Clive Davis also attended the funeral.[81] After the funeral, his body was cremated and the ashes were given to his family.[82]

World / News / Asia / India / Arts / Transcontinental India / Exemplified in Opportunities / Indian Gods / Different ( Resources ) from Web / Protokoll / 13.12.2022

India is a country with diverse heritage and rich culture. It is home to some of the most beautiful folk art traditions! Its folk art is colorful, vibrant, beautiful, and elaborate. You may have noticed that there is a huge amount of Indian folk art that depicts Gods and Goddesses. Religious and mystical elements are essential features of folk art that are not only seen in elaborate paintings but also in other forms of folk art. Some tell their stories, depict their environment, others praise their miracles and valorous deeds. Let’s take a look at a few handpicked Indian folk art that depict Gods and Goddesses.

According to the Hindu view, there are four goals of life on earth, and each human being should aspire to all four. Everyone should aim for dharma, or righteous living; artha, or wealth acquired through the pursuit of a profession; kama, or human and sexual love; and, finally, moksha, or spiritual salvation. This holistic view is reflected as well as in the artistic production of India. Although a Hindu temple is dedicated to the glory of a deity and is aimed at helping the devotee toward moksha, its walls might justifiably contain sculptures that reflect the other three goals of life. It is in such a context that we may best understand the many sensuous and apparently secular themes that decorate the walls of Indian temples.

Hinduism is a religion that had no single founder, no single spokesman, no single prophet. Its origins are mixed and complex. One strand can be traced back to the sacred Sanskrit literature of the Aryans, the Vedas, which consist of hymns in praise of deities who were often personifications of the natural elements. Another strand drew on the beliefs prevalent among groups of indigenous peoples, especially the faith in the power of the mother goddess and in the efficacy of fertility symbols. Hinduism, in the form comparable to its present-day expression, emerged at about the start of the Christian era, with an emphasis on the supremacy of the god Vishnu, the god Shiva, and the goddess Shakti (literally, “Power”).

The pluralism evident in Hinduism, as well as its acceptance of the existence of several deities, is often puzzling to non-Hindus. Hindus suggest that one may view the Infinite as a diamond of innumerable facets. One or another facet—be it Rama, Krishna, or Ganesha—may beckon an individual believer with irresistible magnetism. By acknowledging the power of an individual facet and worshipping it, the believer does not thereby deny the existence of many aspects of the Infinite and of varied paths toward the ultimate goal. Deities are frequently portrayed with multiple arms, especially when they are engaged in combative acts of cosmic consequence that involve destroying powerful forces of evil. The multiplicity of arms emphasizes the immense power of the deity and his or her ability to perform several feats at the same time. The Indian artist found this a simple and an effective means of expressing the omnipresence and omnipotence of a deity. Demons are frequently portrayed with multiple heads to indicate their superhuman power. The occasional depiction of a deity with more than one head is generally motivated by the desire to portray varying aspects of the character of that deity. Thus, when the god Shiva is portrayed with a triple head, the central face indicates his essential character and the flanking faces depict his fierce and blissful aspects.

.By Subhamoy Das